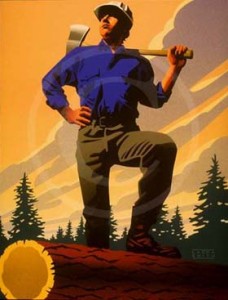

In the words of one 19th century pundit, “You have to let daylight into the swamp before corn and potatoes can grow.” Through most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries Americans idolized loggers as symbols of the rambunctious American determinism that triumphed over this primeval forest. Loggers were our outrageous shock troops that cleared the swamp to liberate land for “Johnnie Farmer.”

After the bitter battles that have raged between the timber industry and our environmental community beginning in the 1970’s it’s hard to recall that we once idealized the rugged the lumberjack. But it wasn’t so long ago that I remember visiting the Oregon Pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York to marvel at the red flannel shirted men that danced across the floating logs. I was so enthralled that I came back repeatedly to sit through their logrolling competitions, the displays of precision falling and the audacious way they scrambled up the bare trunks to perch high above us in the humid New York sky. It was my first encounter with this strange place called Oregon, and the smell of all that wood stayed with me, until the day that I decided to move to that mysterious state out on the far extremities of this continent.

After the bitter battles that have raged between the timber industry and our environmental community beginning in the 1970’s it’s hard to recall that we once idealized the rugged the lumberjack. But it wasn’t so long ago that I remember visiting the Oregon Pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York to marvel at the red flannel shirted men that danced across the floating logs. I was so enthralled that I came back repeatedly to sit through their logrolling competitions, the displays of precision falling and the audacious way they scrambled up the bare trunks to perch high above us in the humid New York sky. It was my first encounter with this strange place called Oregon, and the smell of all that wood stayed with me, until the day that I decided to move to that mysterious state out on the far extremities of this continent.

No matter what you think about the falling of trees, bear with me for a while, as I take you back to the early years of the twentieth century, when everything we did in America was a sparkling success, and few had any doubts about the rightness of our course. We were blessed by being in the right place and at the right time, and our national spirit was so bursting with enthusiasm that we seemed to succeed at everything we touched – or so we thought. We never slowed our enthusiastic pursuit of progress, production and our manifest destiny. And our loggers blazed their way westwards from Maine all the way to Oregon and Washington, where the timber stood so thick it could never be entirely cut – or so we thought.

blessed by being in the right place and at the right time, and our national spirit was so bursting with enthusiasm that we seemed to succeed at everything we touched – or so we thought. We never slowed our enthusiastic pursuit of progress, production and our manifest destiny. And our loggers blazed their way westwards from Maine all the way to Oregon and Washington, where the timber stood so thick it could never be entirely cut – or so we thought.

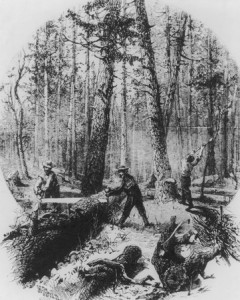

Logging in North America can be traced back to 1631 when the first sawmill was assembled from equipment imported from England at the newly established community of South Berwick, Maine. In those early days there was no distinction between the so-called “lumberers” who felled the trees during the winter months and the “sawyers” that processed them into planks during the summer. By the end of the 1600’s,  the settlers had begun to attack the forests of Maine with such enthusiasm that the British authorities banned logging the best pines and “okes”. These were marked with a Broad Arrow and reserved exclusively for Royal Navy, but enforcement proved impossible as the Northeast and then Maine soon became the center of America’s emerging shipbuilding and wood products industry.

the settlers had begun to attack the forests of Maine with such enthusiasm that the British authorities banned logging the best pines and “okes”. These were marked with a Broad Arrow and reserved exclusively for Royal Navy, but enforcement proved impossible as the Northeast and then Maine soon became the center of America’s emerging shipbuilding and wood products industry.

The invention of the circular saw in 1825 led to ever greater specialization that effectively split the industry, separating those that operated the sawmills from the loggers that supplied the raw materials that they used. And it was this group of rugged characters that would would eventually enter the pantheon of American mythology as the outrageous heroes that literally cut their way through the untamed wilderness to make the  continent safe for the pioneers that followed in their wagons. If it was the US cavalry that cleared the Indians from the plains, it was the lumberjacks that cleared the valleys and hillsides to make way for Johnnie Farmer. It was said in those days that “you have to let daylight into the swamp before corn and potatoes can grow.” And unlike the Mountain men that led the pioneers across the mountains only to see their way of life vanish in a mere 30 years, the death defying lumberjacks barely paused before launching into the seemingly inexhaustible forests of the Pacific Northwest.

continent safe for the pioneers that followed in their wagons. If it was the US cavalry that cleared the Indians from the plains, it was the lumberjacks that cleared the valleys and hillsides to make way for Johnnie Farmer. It was said in those days that “you have to let daylight into the swamp before corn and potatoes can grow.” And unlike the Mountain men that led the pioneers across the mountains only to see their way of life vanish in a mere 30 years, the death defying lumberjacks barely paused before launching into the seemingly inexhaustible forests of the Pacific Northwest.

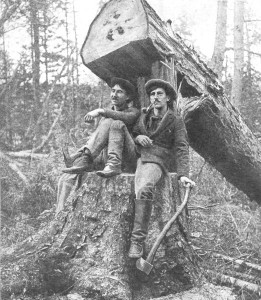

This exuberant phenomenon emerging out of the Maine forests was first captured by C. Lanman, whose 1856 book, Adventures in the Wilds in the United States, describes these early loggers as “a young and powerfully built race of men…genera lly unmarried, and though rude in their manner, and intemperate are quite intelligent. They seem to have a passion for their wild and toilsome life and judging from their dresses I should think possess a fine eye for the comic and fantastic. The entire apparel of an individual consists of a pair of gray pantaloons and two red flannel shirts, a pair of long boots, and a woolen covering for the head, and all these things are worn at one and the same time.”

lly unmarried, and though rude in their manner, and intemperate are quite intelligent. They seem to have a passion for their wild and toilsome life and judging from their dresses I should think possess a fine eye for the comic and fantastic. The entire apparel of an individual consists of a pair of gray pantaloons and two red flannel shirts, a pair of long boots, and a woolen covering for the head, and all these things are worn at one and the same time.”

Stewart Holbrook famously described them as follows, ” Of, say, a crew of fifty green loggers going into the woods in October, about half would find the life too rigorous. They would soon quit and leave. Of those remaining the less alert and sure-footed would be struck by falling timber or crushed flat on a l og landing. The spring drive downriver, the most dangerous of all woods work would surely remove a few more. Once the drive was in, two or three others would die of acute alcoholism or in saloon brawls. As for the few survivors, they were immune to disease and you couldn’t kill them with a pole ax.”

og landing. The spring drive downriver, the most dangerous of all woods work would surely remove a few more. Once the drive was in, two or three others would die of acute alcoholism or in saloon brawls. As for the few survivors, they were immune to disease and you couldn’t kill them with a pole ax.”

Most of the large scale logging in the 19th century took place in Maine, but around the turn of the twentieth century the big operations were already moving on to the virgin forests of Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin.  Logging was best done in the winter, and it was cold in those early forests. The men worked up to fourteen hours out in waist high snow that drifted up amongst the towering black trunks. It was savagely cold in those dark woods, with the timber crackling and booming as the arctic chill gripped the very marrow of the forest.

Logging was best done in the winter, and it was cold in those early forests. The men worked up to fourteen hours out in waist high snow that drifted up amongst the towering black trunks. It was savagely cold in those dark woods, with the timber crackling and booming as the arctic chill gripped the very marrow of the forest.

It was said that “the trees shuddered and quaked when a man with an ax walked among them”. But once a falling wedge had struck home and the tree’s equilibrium began to waver, a deadly hush would sweep through the branches, and the forest would hold its breath as the great giant shuddered, and then went swishing down amongst its brethren to deliver a shuddering blow so profound it was felt more than heard for miles around. After that a silence would fill the empty space and seep outwards to hang heavy above the bluish snow drifts.

bluish snow drifts.

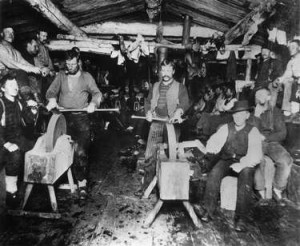

Given the extreme cold most loggers sported thick shaggy beards that covered their exposed faces. Those that didn’t would remove the offending growth using the only razors they owned – the glistening blade of their sharpened axe. Like mythical warriors these rough hewn heroes cherished their axes and would bed down clutching them to their chests, to protect them from the elements. Indeed, the lumberjacks’ camps were crude shelters that barely kept out the elements. The seams between the logs were stuffed with moss and the roofs were covered with bark. The beds were double and triple-decker wooden shelves covered with hay or hemlock boughs. Alongside the bottom tier of bunks ran the “Deacon’s Seat”, a split log bench that ran the entire length of the cabin, along two sides.

In a design reminiscent of Indian long house construction, the fire pit was located in the center of the room, set in sand and stones, and situated under an opening in the roof. Near the door was a grindstone whose nightly spinning would hone their axes to such a wicked edge it split the cold in two.

In a design reminiscent of Indian long house construction, the fire pit was located in the center of the room, set in sand and stones, and situated under an opening in the roof. Near the door was a grindstone whose nightly spinning would hone their axes to such a wicked edge it split the cold in two.

Throughout the long winter nights these New England lumberjacks would patrol their rough forest tracks pouring water on their icy roads which would permit them to slide their logs down to the banks of the local rivers. And there the logs would accumulate until the thawing snow and warming temperatures would break the icy grip on the waterways. Once the spring flood was running high the loggers would discard their axes, launch their logs and leap aboard on to the undulating carpet of timber – poking and prodding as they drove their logs downriver to the mills. The “rivermen” that mastered the art of riding the logs down these tumultuous rapids were revered by all who came to see them sweep down the wild rivers astride a flood of logs. They used to boast about these “rivermen” that you could throw a bar of yellow soap into the water and they would ride the bubbles to shore. Those that survived even a few seasons of successful river runs were veritable cats on the logs. The river made certain of that. If you fell into the boiling white water, awash with a myriad of churning logs, swimming was more pointless than prayer.

the undulating carpet of timber – poking and prodding as they drove their logs downriver to the mills. The “rivermen” that mastered the art of riding the logs down these tumultuous rapids were revered by all who came to see them sweep down the wild rivers astride a flood of logs. They used to boast about these “rivermen” that you could throw a bar of yellow soap into the water and they would ride the bubbles to shore. Those that survived even a few seasons of successful river runs were veritable cats on the logs. The river made certain of that. If you fell into the boiling white water, awash with a myriad of churning logs, swimming was more pointless than prayer.

The Spring river run was the climax in the loggers’ annual cycle when they risked death to deliver their precious cargo and make their annual rendezvous with what really mattered: beautiful women, violently strong liquor and uproarious brawling. Their fighting was less about settling scores than it was for the sheer delight of it. Guns and knives played little part in these protean struggles, but gouging of eyes and the chewing ears earned high praise. It was also highly appropriate for a logger to stomp on his prone opponent in his nail studded “calked boots” tenderizing his torso from neck to groin. This classy move was referred to as “putting the boots to him” and it usually left the recipient somewhat worse for wear.

The Spring river run was the climax in the loggers’ annual cycle when they risked death to deliver their precious cargo and make their annual rendezvous with what really mattered: beautiful women, violently strong liquor and uproarious brawling. Their fighting was less about settling scores than it was for the sheer delight of it. Guns and knives played little part in these protean struggles, but gouging of eyes and the chewing ears earned high praise. It was also highly appropriate for a logger to stomp on his prone opponent in his nail studded “calked boots” tenderizing his torso from neck to groin. This classy move was referred to as “putting the boots to him” and it usually left the recipient somewhat worse for wear.

could you tell me where or what year the picture of the 7 lumberjacks with the musical instruments was taken.

where di dyou see the image?