About 46.5 miles out of Portland on the Sunset Highway (US 26) we reach an important junction on the way to the coast. Most people go flying by the rest area located there, unless the kiddies in the backseat are wailing for a pit stop. But this is the original way into this area, before there was a Wolf Creek Highway, later renamed the Sunset Highway. About 100 yards beyond the entrance to the rest area is a dirt road that leads northwards (to the right) up the Rock Creek Valley and eventually it used to lead to Keasey and Vernonia. This was the route that the railroad loggers used to gain access to the huge stands of trees in the Coastal Range situated south of the “Wolf Creek” highway. The rest area sits to the north of a huge bowl that drains a vast ring of coastal headlands into the North Fork of the Salmonberry River. It was this timber rich landscape that the Oregon American Logging Company had in their sights when they extended their railroad spur #26 across what is now the sunset Highway and began logging in the highest slopes of the Coast Range right above the Lower Nehalem and the Salmonberry River.

By 1948, the Oregon-American Logging Company was operating at the top of the coast range along a rim of forested peaks that loomed above the Lower Nehalem River. Located at the furthest extremity of a narrow ridge jutting over the precipitous slope was Windy Gap, one of the most remote logging sites in the Pacific North west. From this isolated perch the loggers could look over the tops of the last coastal range and see the ships plying their way up and down the Oregon Coast. It was also utterly at the mercy of the violent storms that crashed ashore from the vast stretches of the Pacific Ocean. Only a few months earlier a gargantuan winter storm had lifted the watchman’s cabin right off its foundations and had flung it headlong off its mountain perch.

west. From this isolated perch the loggers could look over the tops of the last coastal range and see the ships plying their way up and down the Oregon Coast. It was also utterly at the mercy of the violent storms that crashed ashore from the vast stretches of the Pacific Ocean. Only a few months earlier a gargantuan winter storm had lifted the watchman’s cabin right off its foundations and had flung it headlong off its mountain perch.

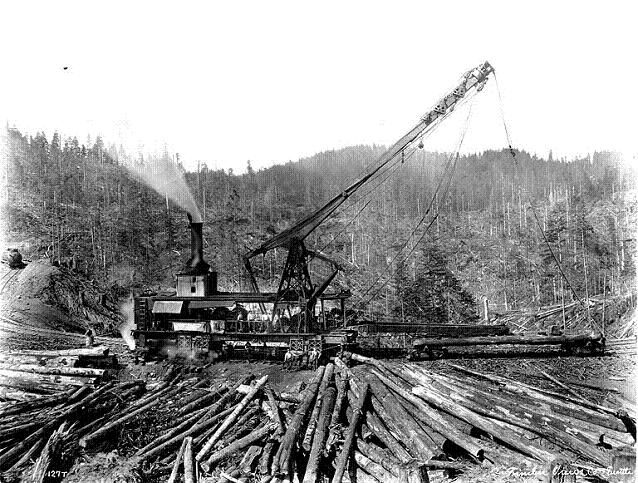

And it was to this remote logging site perched at the top of the Coast range that the Oregon-American Lumber Company had brought the greatest steam punk behemoth of the logging world, a 300 ton Lidgerwood Tower skidder. These huge “aircraft carriers” of the logging business had been developed during the high-balling era of steam logging. With their huge tower extended they could log a 360-degree arc and lift the huge old-growth logs from nearly a mile away and pull them up 3,000 feet in elevation to the waiting rail cars on the ridge high above. It was reported that, “The canyon walls were so steep that the skyline angled down as much as 45 degrees.” All the crane operator could see of the choker setters were their helmets that looked like little specks of grey metal lost in the jungle of massive old growth forests.

On June 3rd, 1948, the Oregon-American Logging company had wrestled this monstrous rail carriage up to the top of the Coa st Range with four locomotives pushing and pulling the Lidgerwood Tower Skidder into position. And from its commanding heights it began to log the practically inaccessible slopes of the Middle Fork of Cronin Creek.

st Range with four locomotives pushing and pulling the Lidgerwood Tower Skidder into position. And from its commanding heights it began to log the practically inaccessible slopes of the Middle Fork of Cronin Creek.

At about 8:30 AM the 104 “lokie” was bringing down an empty oil car and 13 big car-loads of logs down a narrow sinew of iron rail lines snaking along the rim of Windy Gap. Below the slowly descending train clouds flowed over the Coast Range turning the peaks into islands on a vast ocean of fog. And above the creeping train the clear blue sky of that June morning was so close the engineers could almost reach out and grab it.

For the last 25 years until that morning the Oregon-American had managed to haul 2 million board feet of wood out of the Coast Range without a serious railroad accident. And considering the tenuous network and rickety trestles that held this delivery system together – this was no mean feat. But as the train slowly sank through the blanket of clouds and maneuvered its way towards Camp Olsen all that would change.

The train was inching its way down the steep grade of Line Spur 26, but had come to a stop about a mile from Camp Olsen, because the section foreman was making repairs to the track. The braking process brought the train to a halt on a fairly steep slope near the junction with Spur 26-8 . In the locomotive were the Jeff McGregor, the engineer, Jerry Manning, the fireman, and Frank Willis, the time keeper. Three brakemen were riding along further back amongst the carloads of logs. Up to that point everything seemed to in order and there was no apparent cause for concern.

After a short wait the section foreman completed his work and waved the train onwards. But from the moment it started it was clear to all who witnessed the event that the train was picking up speed too quickly. It continued on at an alarmingly increased speed, and as it tried tho round the bend at the 26-8 junction it jumped the track on the curve and overturned immediately. This is where it gets a bit gruesome. George Lee, the head of the construction crew describes the scene with brutal frankness,

The engineer wasn’t alive when I got there. He got half-way out the cab window and that’s as far as he made it. He was cooked. You don’t get two hundred pounds of live steam goin’ on you and survive. . The time keeper ‘ol Frank Willis, he was just squashed right between the boiler and the tank. The other guys, they weren’t squashed, they were just cooked.” – George Lee, from The Oregon American Ain’t No More!

As I try to penetrate past the official perspective that these damage reports present, one does get the sense that the loss of these individuals was a real blow to the heart of the company and to its employees. The five that rode the ill-fated train accounted for more than 120 years of experience in railroad logging experience – an utterly inconceivable feat in this era of volatile career options.

Not surprisingly the company’s reports and it’s semi-official history, The Oregon American Ain’t No More! both draw the conclusion that the cause of the accident will never be known – especially with conflicting reports of the two brakemen and the deceased engineer.

The contemporary Oregon-American internal records quickly move on to explaining how the engine was pulled upright again – so that it tipped right back on the rails. And how most of the damage was insured; The Oregon-American was only at risk for only $5000. By Monday they planned to have the scene cleared and the enough trains moving to keep up the twice daily delivery of 13 car-loads of lumber to the sawmill in Vernonia. The 104 was eventually repaired and rejoined the service. The same cannot be said of Jeff McGregor, the engineer, Jerry Manning, the fireman, and ol’ Frank Willis, the timekeeper.

Harvesting logs near the ceiling of the Coast Range was and remains a bodacious undertaking. In the heady days of the post-war reconstruction period, timber companies were regrowing their labor force and were high-balling production. These were the days of the “boomers”, the “short stake artists”, “gyppos” and career loggers, but as this story relates – it was still a dangerous business being a steam engine logger.

One can imagine what the workers were feeling as they returned to work so soon after that ghastly accident.

George Lee, the construction chief, was the one that had to do the clean-up and recovery of the bodies. He tells it this way,

“When it happened I was building the road into Camp Olsen. Here come Andy. He was VERY upset. ‘Yorge,’ he says, ‘we had a big accident.’ Gesturing toward the head of the valley, he continued in the typically Scandinavian accent so common among many of the Finns and Swedes that worked the woods in those days, ‘104 tipped over up there. We need the crane. We need the bulldozer. Come on with me!’

George continues, “Them three guys were still in there yet. I had to put the cat line around the 104’s oil tank to pull it away from the boiler to get ’em out. Then my helper and I packed them out and laid ’em in a row there. I inherited that job, packing them guys out of that. Didn’t like it either!”

Two of the brakemen that survived the crash were too upset to make statements for the Clatsop County coroner. The third skedaddled and never showed up to make a statement.

It must have been hard on all of them considering that up until that point they had been operating in the area for over 25 years and had hauled out about 2 billion feet of logs without any significant loss of life, and then in one morning they lost three of their railroaders in this gruesome manner.

I actually went to the wreck of the 104 as my Father had been an Engineer for a number of years. He was commissioned to give a reflection of what he personally believed had happened. I knew Jerry Manning. It was a terrible accident.

Joe Doyle along with Chet Alexander had worked for OA from 1925 until 1946. Chet continued up until 1958 piking up steel and closing the railroad activity.

Fred Hagamen ,Joe Doyle and myself took the 102 to Vernonia on its last trip. 1957

I was raised in Camp McGregor and cherish my vivid memories.

I worked for Oregon-American, both in the woods and in the mill. My mother told me Fred Hagerman was a boarder in our house when I was a child. I have no memory of that. I think it was 1948 that I worked for O-A in the woods and we did not wear “hard hats” in those days. I have a photo of George Lee and also of the engineer on the O-A 105 engine, Chet Alexander.