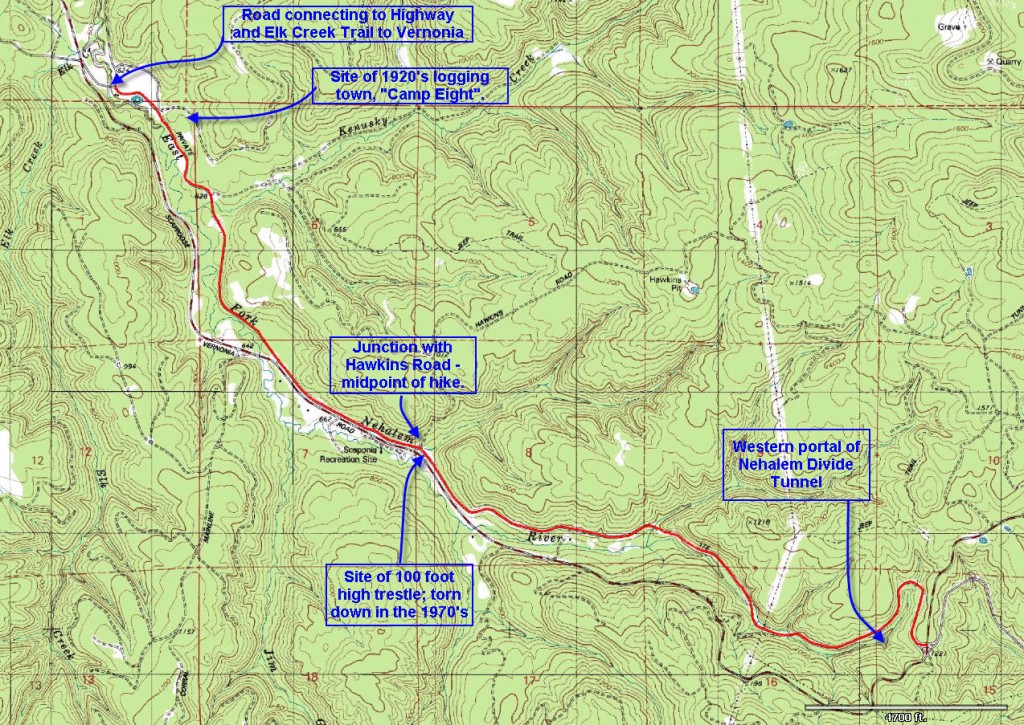

Distance: 5.54 miles

Walk duration: 3 hours

Travel time to trail head: 47 minutes (32 miles) to summit of Scappoose/Vernonia Rd.

Elevation change: 643 ft drop in elevation from the summit (1295′) to Elk Creek (652′). Mid-point at Hawkins road is at 700′ elevation.

Brief summary: This segment of the Scappoose to Vernonia Trail descends westwards from the summit all the way to Elk Creek, where the trail crosses the county road and climbs over the ridge to Vernonia.

The trail passes through mostly forested areas with some open areas (location of Camp Eight) further down in the Nehalem Valley. The hike is along the Crown Zellerbach road that is being gradually restored by Columbia County to connect with the Banks to Vernonia linear trail.

Trail Log: The recommended approach to this segment of the trail is to commence at the summit and walk downhill to Elk Creek.

There is ample parking at the turn-out at the summit of the Scappoose to Vernonia road. The ramp down to the CZ trail begins at the east side of the turnout behind a large pile of rocks and drops down to the east of the bridge. Once down to the logging road, turn left to pass under the county road bridge and continue westwards making a big bend to the north. Not far from the beginning of the trail there is an obscure

track on the left that leads down to the bottom of the ravine to the western portal of the Nehalem Divide Tunnel (see Summit to Spitzenberg segment for full description of the rail road and tunnel).

Most of the higher elevations of this road are in nearly mature conifer forests. The county has been working to keep the culverts repaired so that the constant threat of wash outs is diminished, unless of course the forest eats your equipment…The last time I walked this trail I encountered a hunter and we got to talking about cougars in these woods. He thought that perhaps it was their voracious appetite for deer that was the cause of his inability to bag his buck. And so I got to thinking and researching…

Cougars:

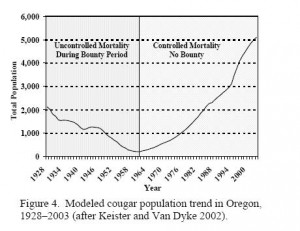

There are currently about 5,700 cougars in Oregon which greatly exceeds historical populations. Indeed, cougars have not always fared so well in the region. Cougars evolved as a distinct species about 390,000 years ago, but it is thought they went extinct in North America during the late Pleistocene Era (10,000–12,000 years ago). Our current cougar populations are probably the result of natural re-colonization from surviving cougars in Central and South America.

There are currently about 5,700 cougars in Oregon which greatly exceeds historical populations. Indeed, cougars have not always fared so well in the region. Cougars evolved as a distinct species about 390,000 years ago, but it is thought they went extinct in North America during the late Pleistocene Era (10,000–12,000 years ago). Our current cougar populations are probably the result of natural re-colonization from surviving cougars in Central and South America.

During the opening of the Oregon territory cougars were common throughout most of our forested lands. In Oregon’s early history these stealthy hunters were considered the arch-villains of our landscape and were hunted ferociously. Settlers, burgeoning timber and agricultural penetration brought our two species into increased conflict and by 1843 we had declared war on the cats issuing a $10 bounty for each slain cougar. For the next 124 years bounties and unregulated destruction took a toll on the cougar population causing cougars to decline markedly through the late 1960s. Most cougar hunting occurred during the winter’s snowy season when they could be tracked more readily, so increased logging road penetration and the development of snowmobiles during the 1960’s increased the reduction in cougar populations so that it became necessary to eliminate bounties and regulate hunting cougars  by 1967. The tide began to shift backing the favor of the cougars in 1994 when a citizens’ ballot initiative passed making it unlawful for hunters to pursue cougars with dogs. Currently the state’s cougar management plan calls for the maintenance of a target population of 3,000 cougars, but the elimination of dog-assisted hunting has decreased the annual “take” so that the populations are once again thriving.

by 1967. The tide began to shift backing the favor of the cougars in 1994 when a citizens’ ballot initiative passed making it unlawful for hunters to pursue cougars with dogs. Currently the state’s cougar management plan calls for the maintenance of a target population of 3,000 cougars, but the elimination of dog-assisted hunting has decreased the annual “take” so that the populations are once again thriving.

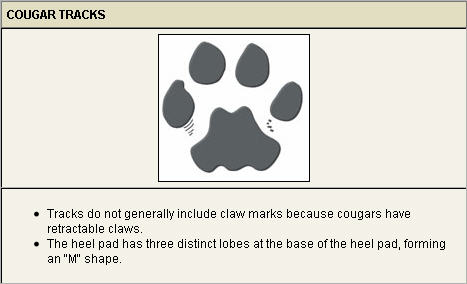

Much of northwest Oregon appears too densely forested to provide optimal habitat for stalking, but there are areas with just the right combination of habitat and prey populations that can sustain high numbers of cougars. Cougars much prefer rock outcroppings and/or downed logs beneath a forested canopy to bed down. During winter, cougars avoid areas of deep snow. Instead, they frequent forests with multi-storied canopy cover where the snow is not as deep, and where their prey  is more abundant. In Oregon’s North Coast range the cougar population density is almost 4 cougars in every 100 square miles (mi2). To put that into perspective imagine that a 5.5 mile hike neatly bisects a square of land that is as wide as your hike is long. This 31 square miles of forest is likely to host at least one cougar. Are you looking over your shoulder yet?

is more abundant. In Oregon’s North Coast range the cougar population density is almost 4 cougars in every 100 square miles (mi2). To put that into perspective imagine that a 5.5 mile hike neatly bisects a square of land that is as wide as your hike is long. This 31 square miles of forest is likely to host at least one cougar. Are you looking over your shoulder yet?

Cougars generally hunt at night beginning near dusk. On average cougars kill one deer or elk every 7 to 8 days. Females with young kill more often than a lone cougar. Where both elk and mule deer were present, female cougars tended to kill mule deer, whereas males tended to prefer killing elk. Maintaining healthy elk and deer populations ensures an adequate prey base for sustainable cougar populations. Forest management activities that increase forage for deer and elk also benefit cougars.

On private timberlands, which are predominating in the coastal range, timber harvesting has become much more intensive. The result is less forage available on both public and private forestlands for deer and elk.

Elk populations could decline over the next several decades within the zone if the forage base continues to decline because of unsustainable forest harvesting. Deer throughout the coastal areas have also shown a declining trend for many years. As with elk, the forage base necessary to support deer appears to be declining as a result of changes in forest management on public and private lands. ODFW does not believe cougar predation is the primary factor affecting deer populations at this time.

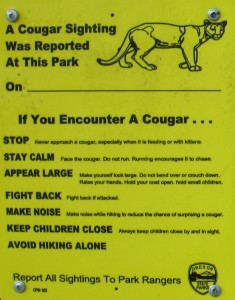

It’s very unlikely that you will see a cougar in the woods. But what should you do if you do encounter a cougar?

- Cougars often will retreat if given the opportunity.

- Leave the animal a way to escape.

- Stay calm and stand your ground.

- Maintain direct eye contact.

- Pick up children, but without bending down or turning your back on the cougar.

- Back away slowly.

- Do not run. It can trigger a chase response in cougars.

- Raise your voice and speak firmly.

- Raise your arms to make yourself look larger and clap your hands.

- If a cougar does attack you, fight back with rocks, sticks, tools or anything available. There has never been a fatal cougar attack on a human in Oregon.

The 100 ft high Trestle:

About 1.15 miles from the summit, you may spot a trail veering off to your left and dropping down into the ravine. This rough track connects with the county road that descends on the opposite wall of this valley. Just a bit further you will pass under some power lines.

The upper elevations of this valley can be absolutely brilliant in the fall fall as the nearby picture can attest.

At the base of this valley we arrive at Hawkins Rd. where we briefly rejoin the county road to cross the unnamed creek. This is also a good mid-way access point for those that need a shorter (3.1 mile) hike, or will double back to the summit – making it a 6.2 mile loop.

As we proceed westwards down the East Fork of the Nehalem River past the Hawkins Road junction, the CZ Trail parallels the county road quite closely.  A quarter of a mile east of the Hawkins road junction you will be able to see the entrance to the Scaponia County Park on the far side

A quarter of a mile east of the Hawkins road junction you will be able to see the entrance to the Scaponia County Park on the far side of the county road. Another quarter mile brings you to an idyllic little meadow nestling a lovely log cabin amongst the trees.

of the county road. Another quarter mile brings you to an idyllic little meadow nestling a lovely log cabin amongst the trees.

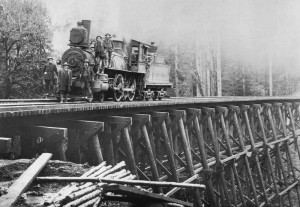

As you descend towards the meadow, you are walking under what was once one of the highest wooden trestles ever built. It was at this point that the across this creek that Henry Turrish built one the worlds highest trestle bridges ever constructed. This 100′ tall wooden edifice that conveyed the “Portland & Southwestern” over an unnamed creek and the boggy floor of the valley survived well the 1970’s, but was ordered to be dismantled shortly after the County built Scaponia County Park nearby. From an elevation of around 705 ‘ it extended for nearly a mile to connect with the height of land on the downhill side at 704’ in elevation. It is said that the sides of the trail in this area are littered with railroad nails.

shortly after the County built Scaponia County Park nearby. From an elevation of around 705 ‘ it extended for nearly a mile to connect with the height of land on the downhill side at 704’ in elevation. It is said that the sides of the trail in this area are littered with railroad nails.

Also of particular note here are some of the best examples of the Oligocene fossil deposits. As you walk down this slope, just opposite the log cabin look for outcroppings on the north side of the trail. According to a 1957 DOGAMI report these fossil beds are continuously exposed for several hundred feet. Another outcropping can be found at the west end of the county bridge that crosses the east Fork of the Nehalem River a short distance to the west of the little log cabin pictured above. The CZ Trail and the county road run parallel for most of this distance, and are separated by a gate at the lower end of this slope. A short jaunt down the county road to the bridge will bring you to the fossil deposits located 30 feet above the highway on a steep slope above the west end of the bridge.

The descriptions of this are from the 1957 DOGAMI report mention several trestles. But today the route bends around a ridge, and soon begins to drop down to Kenusky Creek. Since the P&SW was sold to the Clark & Wilson Railroad in 1926 it was soon integrated into the vast network of logging railroads that the Clark & Wilson operated in the North Coast range. Consequently the original route of this line did descend to and cross Kenusky Creek, but then it climbed the ridge line to connect with the other lines in the area – instead of continuing down the valley floor. It wasn’t until after 1929 that the Clark & Wilson extended the line down the valley and out to Pittsburg. The Clark & Wilson Railroad continued to operate this network of rural logging lines until 1944 when it was sold to Crown Zellerbach, who converted most of these grades for truck logging.

Kenusky Creek. Since the P&SW was sold to the Clark & Wilson Railroad in 1926 it was soon integrated into the vast network of logging railroads that the Clark & Wilson operated in the North Coast range. Consequently the original route of this line did descend to and cross Kenusky Creek, but then it climbed the ridge line to connect with the other lines in the area – instead of continuing down the valley floor. It wasn’t until after 1929 that the Clark & Wilson extended the line down the valley and out to Pittsburg. The Clark & Wilson Railroad continued to operate this network of rural logging lines until 1944 when it was sold to Crown Zellerbach, who converted most of these grades for truck logging.

Camp Eight:

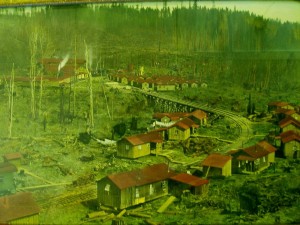

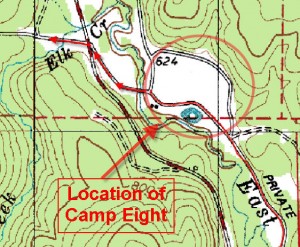

About two miles from Hawkins Road, or 5 miles from the summit the CZ Trail enters a flat plain tucked into a broad bend in the flanking hills. It was at this location that the Clark & Wilson railroad and their logging interests erected Camp Eight to serve as residential area for their loggers. Probably built in 1928, the site became a burgeoning little town because it occupied an open flat area and it was located near a major fork in the railroad.

About two miles from Hawkins Road, or 5 miles from the summit the CZ Trail enters a flat plain tucked into a broad bend in the flanking hills. It was at this location that the Clark & Wilson railroad and their logging interests erected Camp Eight to serve as residential area for their loggers. Probably built in 1928, the site became a burgeoning little town because it occupied an open flat area and it was located near a major fork in the railroad.  As mentioned above, the Portland & Southwestern spur that climbed the nearby ridge linked it to the Clark & Wilson line that headed east to another major logging camp called Wilark, and eventually it’s own log dump on the Columbia River. Originally, logging companies had housed loggers in railroad cars that were parked near the logging sites. These railroad logging camps were tightly controlled by the company, and workers could only “escape” their quarters from Saturday evening through Sunday—if they could

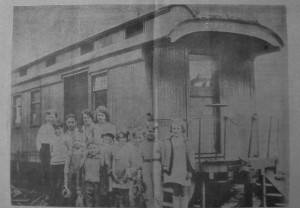

As mentioned above, the Portland & Southwestern spur that climbed the nearby ridge linked it to the Clark & Wilson line that headed east to another major logging camp called Wilark, and eventually it’s own log dump on the Columbia River. Originally, logging companies had housed loggers in railroad cars that were parked near the logging sites. These railroad logging camps were tightly controlled by the company, and workers could only “escape” their quarters from Saturday evening through Sunday—if they could afford the trip to “town.” By the 1920s the companies began to build detached homes where the workers lived in a company owned community and commuted to their work sites on the trains that hauled out the wood. Amenities were scarce as this picture of the railroad-based school for the children of Camp Eight illustrates. By the end of 1931 loggers were earning about $4.00 per day! Grace Brandt Martin, the school mistress at the nearby Wilark Camp in 1931 described the typical accommodations,

afford the trip to “town.” By the 1920s the companies began to build detached homes where the workers lived in a company owned community and commuted to their work sites on the trains that hauled out the wood. Amenities were scarce as this picture of the railroad-based school for the children of Camp Eight illustrates. By the end of 1931 loggers were earning about $4.00 per day! Grace Brandt Martin, the school mistress at the nearby Wilark Camp in 1931 described the typical accommodations,

“The weather-beaten shack that we are to occupy has never been painted on the outside, just like all the other houses  I saw around the camp. In the small Kitchen there is a sink piped for cold water and the only, places for storing things are a few crudely built shelves. The bedroom is about the same size as the kitchen, so there is just enough room for a double bed, dresser, and my wardrobe trunk. No closet, naturally, but a makeshift place to hang clothes has been built in one corner.”

I saw around the camp. In the small Kitchen there is a sink piped for cold water and the only, places for storing things are a few crudely built shelves. The bedroom is about the same size as the kitchen, so there is just enough room for a double bed, dresser, and my wardrobe trunk. No closet, naturally, but a makeshift place to hang clothes has been built in one corner.”

Crossing the County Road:

At Camp Eight, or at that broad expanse that now remains, we will leave the main trail that follows the East Fork of the Nehalem River and cross over to the county Road, using what remains of an old railroad bridge. That same bridge crossing the East Fork is visible in the above picture of Camp Eight. It was subsequently turned into a truck road after Crown Zellerbach Corporation bought these operations in 1944.

At Camp Eight, or at that broad expanse that now remains, we will leave the main trail that follows the East Fork of the Nehalem River and cross over to the county Road, using what remains of an old railroad bridge. That same bridge crossing the East Fork is visible in the above picture of Camp Eight. It was subsequently turned into a truck road after Crown Zellerbach Corporation bought these operations in 1944.

Once across the east Fork of the Nehalem the road crosses the county Road. On the far side the road continues but is blocked by a gate and by a huge berm that marks the end of the road. Beyond it flows Elk Creek and on the far side you can see the road head up the ridge – but that’s for the next hike…

when i was in boy scouts in scappoose in the late 1960’s we used to camp at scaponia park and climb the old railroad trestle on the opposite side of the scappoose vernonia highway and dig for sea shell fossils under the trestle.Now I cannot remember where the fossils were nor can i locate it.Is it to the right towards scappoose or to the left towards the vernonia junction.I know it is on the opposite side of the road from scapponia park.I used to live in chapman and grew up in Scappoose.I was watching OPB last nite and saw a segment on what you are doing about finding trails etc in the coast range.Any help u could give on the fossil location near the park would be appreciated

I know that there are good fossil beds in this area. Check the blog section of this site for an article I wrote called “Mud is us” and it gives several other sites in the vicinity. But as to the specific site you’re referring to, I believe the best locations would be to the west (left) of Scaponia. The trestle used to extend to the west of Scaponia, down along the section of road that is opposite the cute little log cabin situation on the south side of the road. I would dig into the embankment along that stretch of the path to find what you’re looking for.

Jim

Portland & Southwestern spur that climbed the nearby ridge linked it to the Clark & Wilson line that headed ~~west~~ to another major logging camp called Wilark, and eventually it’s own log dump on the Columbia River.

Do you mean East ? I’m trying to find the actual location of Wilark- the only thing I have been able to find is a dubious Lat / Long of a “Historic” post office at the Southern tip of camp 8.

Jeff:

You’re right. From Camp Eight Wilard is located to the Northeast, on the north side of Bunker Hill. So it should read “east, or more accurately Northeast. I’ll make the correction in the text. Thanks for catching the error.

Jim Thayer