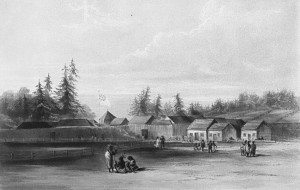

No doubt it was a blustery winter day, with the cold drafts seeping through the chinks in the log cabin walls, when Dr. McLoughlin decided that Fort Vancouver needed a sawmill to produce proper planks and board. Since it’s establishment in 1824, Fort Vancouver’s population had grown exponentially to accommodate its growing and diversifying populace. After four years Dr. John McLoughlin presided over a motley crew of fellow Hudson Bay Company colleagues, scores of French Canadian voyageurs, quite a few Iroquois and Cree Indians, and around 300-400 Hawaiians and their native wives.

For the last several years Dr. McLoughlin and his employees had been hard at work felling trees, stripping the bark and building the numerous homes and log cabins that housed the burgeoning establishment. But now they needed planks and boards. So in 1828, Dr. McLoughlin called upon William Cannon to find a suitable location to build a sawmill . Eventually, Cannon settled on a location seven miles east of Fort Vancouver, where he build the settlement’s first sawmill. There he and a crew of 25 Hawaiians, set to work processing the logs that were dragged out of the forests. In short order they were turning out nearly 1,500 board feet per day – more than what was needed by the fort.

No less than a year later , in January 1829, the first shipment of lumber was loaded on to The Cadboro, destined for Oahu. In those days it could take sailing vessels as long as two months to reach the mouth of the Columbia, but once through the bar at Astoria the trip to Oahu would only take another 10 days to three weeks – a relatively short period of time compared with the 5 months sailing schedule to reach London. Undoubtedly, Dr. McLoughlin, the Fort’s Chief Factor would have been on hand to bid his friend Captain Aemilius Simpson farewell as he  departed with the Fort’s inaugural shipment of wood destined for the Sandwich Island. All in all, Dr. McLoughlin should have been pretty pleased with his efforts to expand the fort’s productivity. Not only was the fort now entirely self-suficient in foodstuffs, but with the departure of the Cadboro, McLoughlin was initiating a lucrative new export relationship that would eventually trade not just lumber, but also hay, wheat, potatoes, and salmon to Hawaii, California and the Russian enclaves in Alaska.

departed with the Fort’s inaugural shipment of wood destined for the Sandwich Island. All in all, Dr. McLoughlin should have been pretty pleased with his efforts to expand the fort’s productivity. Not only was the fort now entirely self-suficient in foodstuffs, but with the departure of the Cadboro, McLoughlin was initiating a lucrative new export relationship that would eventually trade not just lumber, but also hay, wheat, potatoes, and salmon to Hawaii, California and the Russian enclaves in Alaska.

In 1834 a second sawmill was erected. Employing about 25 people, mostly Hawaiian Islanders, and production increased from 1,500 board feet to over 3,500 board feet per day. Ten or twelve yoke of oxen were used to haul logs to the mill and move the finished lumber to the banks of the Columbia. There they were assembled into rafts and floated down to the Fort or were loaded directly onto ships for export. Dr. John McLoughlin’s sawmill continued to operate until it was purchased by American interests in 1848, but by then commercial logging and saw milling had shifted to the burgeoning American community clustered at the foot of the Willamette Falls in Oregon City.

board feet per day. Ten or twelve yoke of oxen were used to haul logs to the mill and move the finished lumber to the banks of the Columbia. There they were assembled into rafts and floated down to the Fort or were loaded directly onto ships for export. Dr. John McLoughlin’s sawmill continued to operate until it was purchased by American interests in 1848, but by then commercial logging and saw milling had shifted to the burgeoning American community clustered at the foot of the Willamette Falls in Oregon City.

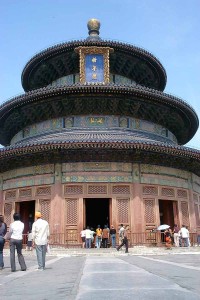

The commodity trade that Dr. McLoughlin developed would far outlive both the Fort and Hudson Bay Company’s involvement in trading. The quality and quantity of lumber coming out of the Pacific Northwest was such that it soon created a demand far beyond the shipyards of Oahu. Merchants from California to China were soon clamoring for “Columbia wood” with which to build the Gold Rush communities in California, and even some of the palaces and temples in the China, including the famous Temple of Heaven in Beijing. In the late Twentieth Century, the Japanese were renowned for their appreciation of Oregon “old growth” timber, and their timber import facility at Shinkiba was awash with finest logs pulled from Oregon’s coastal forests.