Upon reading my materials and observations on the Oregon Coast Range the question frequently arises as to what distinguishes my perspectives on this landscape from that of others. I can’t say I really thought much about this while I was busily wearing out my hiking boots. But perhaps my thirst for exploring our trackless wilderness is a bit out of the ordinary, or else I would have encountered more like-minded spirits.

Upon reading my materials and observations on the Oregon Coast Range the question frequently arises as to what distinguishes my perspectives on this landscape from that of others. I can’t say I really thought much about this while I was busily wearing out my hiking boots. But perhaps my thirst for exploring our trackless wilderness is a bit out of the ordinary, or else I would have encountered more like-minded spirits.

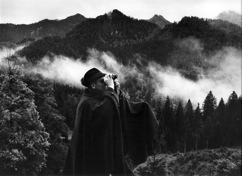

But my proclivity for getting lost in the woods is not something new. I grew up deep in the Bavarian Alps surrounded by precipitous peaks. In the winter the mountains blocked the sun for much of the day, and the avalanches roared into the valley whenever we had a heavy snowfall. Mountains loomed large in my youth, as the home of mysterious folk-lore spirits, as an inviting network of precarious cliff clinging goat trails, an unending inventory of musty caves to be explored, a trove of abandoned World War II arms caches and a playground of lofty eyries

Bavarian Alps surrounded by precipitous peaks. In the winter the mountains blocked the sun for much of the day, and the avalanches roared into the valley whenever we had a heavy snowfall. Mountains loomed large in my youth, as the home of mysterious folk-lore spirits, as an inviting network of precarious cliff clinging goat trails, an unending inventory of musty caves to be explored, a trove of abandoned World War II arms caches and a playground of lofty eyries  from which to view the world beyond my valley. Constantly warned off these perilous slopes by my cautious parents, I was not to be deterred from crawling up the most precarious faces and poking into every crevasse to tease out the myriad secrets these crags had to offer. There was something in me that reveled in the experience of being beyond the orderly reach of civilization. In my passionate teen years I was given to reciting Lord Byron’s romantic verse from the top of mountain peaks. Somehow the thrill of the claiming for myself these secret places deep in the forest or high up on the forbidden rock faces was a romantic urge that never quite left me…

from which to view the world beyond my valley. Constantly warned off these perilous slopes by my cautious parents, I was not to be deterred from crawling up the most precarious faces and poking into every crevasse to tease out the myriad secrets these crags had to offer. There was something in me that reveled in the experience of being beyond the orderly reach of civilization. In my passionate teen years I was given to reciting Lord Byron’s romantic verse from the top of mountain peaks. Somehow the thrill of the claiming for myself these secret places deep in the forest or high up on the forbidden rock faces was a romantic urge that never quite left me…

Having grown up amongst Europe’s Celtic runes, the roman roads and the gothic churches, evidence of history’s long sweep was commonplace. So I was always a bit baffled by the reverence my friends and relatives from America felt in visiting the local castle. But when I came to Oregon and beheld for the first time the vast and empty spaces of eastern Oregon, I felt a similar awe. And every time I walk deep in the forests, I am reminded of how little time has past since this land was completely primeval. Where European civilization emerged from the woods and marshes well over 2000 years ago, here in the Pacific Northwest man has only just emerged from the domination of our colossal rain forests. Standing deep in the Oregon’s coastal forests, amongst the noble Western Cedars, beneath the huge Sitka Spruce giants and the ubiquitous Douglas fir I feel as if I am transported back in time to a time when men’s mark on nature was still fresh. These are literally the densest forests on earth, and their dark loamy environment fed by nutrient rich high latitude ocean weather simply reeks with life. In the dark and close confines of Oregon’s coastal forest life as we know it ceases and the rules are reversed. Hundreds of people have been lost in these forests, never to reappear. Planes go down into the forest canopy and it closes around the wreckage forever hiding the remains. Even DB Cooper and all his loot was swallowed alive. Apply your sensible Boy Scout wisdom about following water to safety and it will most assuredly lead you to your doom in this primeval jungle. Civilization simply does not penetrate into these remote ravines. When I am in the deep forests and utterly alone, it’s exhilarating to think back to a time thousands of years ago when we had not yet mastered our environment and were still inexorably subject to the whims of nature.

reverence my friends and relatives from America felt in visiting the local castle. But when I came to Oregon and beheld for the first time the vast and empty spaces of eastern Oregon, I felt a similar awe. And every time I walk deep in the forests, I am reminded of how little time has past since this land was completely primeval. Where European civilization emerged from the woods and marshes well over 2000 years ago, here in the Pacific Northwest man has only just emerged from the domination of our colossal rain forests. Standing deep in the Oregon’s coastal forests, amongst the noble Western Cedars, beneath the huge Sitka Spruce giants and the ubiquitous Douglas fir I feel as if I am transported back in time to a time when men’s mark on nature was still fresh. These are literally the densest forests on earth, and their dark loamy environment fed by nutrient rich high latitude ocean weather simply reeks with life. In the dark and close confines of Oregon’s coastal forest life as we know it ceases and the rules are reversed. Hundreds of people have been lost in these forests, never to reappear. Planes go down into the forest canopy and it closes around the wreckage forever hiding the remains. Even DB Cooper and all his loot was swallowed alive. Apply your sensible Boy Scout wisdom about following water to safety and it will most assuredly lead you to your doom in this primeval jungle. Civilization simply does not penetrate into these remote ravines. When I am in the deep forests and utterly alone, it’s exhilarating to think back to a time thousands of years ago when we had not yet mastered our environment and were still inexorably subject to the whims of nature.

My father was an ex-US diplomat who made a living writing books about diplomacy, novels about spies and articles about hunting and fishing throughout central Europe and Asia. He and my mother managed two hunting reserves in Bavaria and in Austria. That meant we spent almost every dawn and dusk in the woods observing the movement of the deer, roebucks and chamois – learning their territories, tallying the game and planning how to cull the herds during the fall hunting season. In the summer we maintained our hunting cabins, as much of the reserve was too high and remote to reach by car, and in the winter we skied up to the feeding stations to dispense the hay. In my early teens I was taught to track, spot and identify animals with a fair degree of accuracy – since we kept a running inventory of all the game based on individual sightings – and I was an essential part of that summer-long effort. In the Alps hunting co-exists alongside high altitude cattle management, selective logging, mushroom gathering, tourism and border patrolling, so I was constantly talking with the upland farmers, the foresters, the old women who stalked  the chanterelles, and the border patrol to learn more about the movement of our herds. Unlike the United States there was a symbiotic relationship between all these parties and we learned from each other even as we crossed paths high up in the range. Since logging was done selectively the impact to the wildlife was minimal, our control of the game population protected the farmers’ crops, and our concealed mountain trails served the mushroom scavengers and foresters to climb the steep slopes. Thus I came to consider the forest from many angles and to appreciate the interwoven network that sustained this delicate ecosystem.

the chanterelles, and the border patrol to learn more about the movement of our herds. Unlike the United States there was a symbiotic relationship between all these parties and we learned from each other even as we crossed paths high up in the range. Since logging was done selectively the impact to the wildlife was minimal, our control of the game population protected the farmers’ crops, and our concealed mountain trails served the mushroom scavengers and foresters to climb the steep slopes. Thus I came to consider the forest from many angles and to appreciate the interwoven network that sustained this delicate ecosystem.

Perhaps the most poignant lesson I learned about this symbiotic relationship and the meaning of stewardship occurred one summer when I was 10 years old and had brought back some firecrackers from the US. With the intensity only a 10 year old can muster I laid siege to a giant ant pile behind the neighboring farmer’s barn. When my pyrotechnics exploded scattering a full third of the heap, the farmer’s wife appeared and read me the riot act for my want on destruction of this ant pile. It seems that the family bible, handed down from generation to generation, had reported faithfully on this insect colony that had sprung up alongside the new farm when it was founded in 1060 AD!

on destruction of this ant pile. It seems that the family bible, handed down from generation to generation, had reported faithfully on this insect colony that had sprung up alongside the new farm when it was founded in 1060 AD!

I was surprised to find that in Oregon there existed an almost adversarial relationship between all these parties, each vying to harvest one part of the ecosystem, with little regard to the impact for others and without any comprehensive sense of stewardship for the overall health of the habitat over the coming decades and centuries. For me the forest cannot be seen in isolation or even from one perspective at a time – it is inextricably linked to the communities around it, the ecology inside, the geology underneath and subject to the weather wafting through it.

Stop and listen the next time you are deep in the woods – to the multilayered saga being told all around you. Hear the grandiose themes of geological transformation, the infi nitely complex life and death dance that sustains fish, fowl, fur and flower. While you are knee deep in the crunchy spring snow, can you hear the distant cacophony of human destruction, or sense the microcosmic drama of 16,000 invertebrates living beneath your every footstep? This is a world that runs itself, no batteries needed. It is both off the grid, and it is the only grid. Like a blind man groping around the edges of an unfamiliar object, I come here to feel the limits of our influence and to understand the real shape of things.

nitely complex life and death dance that sustains fish, fowl, fur and flower. While you are knee deep in the crunchy spring snow, can you hear the distant cacophony of human destruction, or sense the microcosmic drama of 16,000 invertebrates living beneath your every footstep? This is a world that runs itself, no batteries needed. It is both off the grid, and it is the only grid. Like a blind man groping around the edges of an unfamiliar object, I come here to feel the limits of our influence and to understand the real shape of things.

I recognise you.

Lovely prose.

M.