The recent movie “Contagion” depicts a world beset by a terrifying disease that threatens to unravel the world as we know it. The New Yorker review sums it up, “As panic engulfs the country, civil society dissolves. Crowds assault banks and stores; people desperate for a cure attack pharmacies. The episodes are violent and appalling but mercifully brief.”

The recent movie “Contagion” depicts a world beset by a terrifying disease that threatens to unravel the world as we know it. The New Yorker review sums it up, “As panic engulfs the country, civil society dissolves. Crowds assault banks and stores; people desperate for a cure attack pharmacies. The episodes are violent and appalling but mercifully brief.”

But thank goodness this is Hollywood, and none of this happened, right? Many movie-goers were skeptical of whether a disease could have such a widespread impact as the 30% mortality rate cited in the movie. Yet right here in the Pacific Northwest we experienced an epidemic that reached mortality rates approaching 90% of the population.

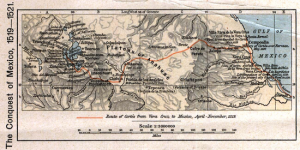

When did this happen, and why are we not aware of it? Well, historians have only recently in the last few decades been able to document the dramatic die-off that occurred long before most Europeans arrived in the interior of this continent. In fact the epidemic that swept through the Americas started almost the moment that the European stepped off their boats in Hispaniola. The first outbreak of smallpox in the Americas was recorded in Hispaniola in 1518. It killed a third of the native population before jumping to the other islands. In 1520 Cortez attacked the Aztecs and his Lieutenant Panfilo de Narvaez landed near the contemporary city of Vera Cruz.

When did this happen, and why are we not aware of it? Well, historians have only recently in the last few decades been able to document the dramatic die-off that occurred long before most Europeans arrived in the interior of this continent. In fact the epidemic that swept through the Americas started almost the moment that the European stepped off their boats in Hispaniola. The first outbreak of smallpox in the Americas was recorded in Hispaniola in 1518. It killed a third of the native population before jumping to the other islands. In 1520 Cortez attacked the Aztecs and his Lieutenant Panfilo de Narvaez landed near the contemporary city of Vera Cruz.  Among his troops was an African slave named Francisco Eguia, who had small pox. The disease quickly spread to the native population and swept through the Aztecs capital, Tenochtitlan. From there it moved south all the way to the Inca empire where it ravaged the population in 1533, 1535, 1558 and 1565. One of the witnesses recalled that, ” they died by the scores and hundreds. Villages were depopulated. Corpses were scattered over the fields or piled in the houses or huts.” And afterwards they were further reduced by successive waves of influenza, typhus, diptheria and measles. The scholar Henry Dobyens estmates that it killed 9 out of ten of the Incas.

Among his troops was an African slave named Francisco Eguia, who had small pox. The disease quickly spread to the native population and swept through the Aztecs capital, Tenochtitlan. From there it moved south all the way to the Inca empire where it ravaged the population in 1533, 1535, 1558 and 1565. One of the witnesses recalled that, ” they died by the scores and hundreds. Villages were depopulated. Corpses were scattered over the fields or piled in the houses or huts.” And afterwards they were further reduced by successive waves of influenza, typhus, diptheria and measles. The scholar Henry Dobyens estmates that it killed 9 out of ten of the Incas.

The first documented pandemic swept north from Guatemala in the late 1770’s. By 1780 it had reached the Navaho pueblos in New Mexico. From there it moved on to the Comanches who traded with their linguistic cousins the Shoshones and Crows. The Shoshones’ traditional territory bridged the Rockies where they traded both with the Blackfeet on the Plains and with the Kootenai and Piegan Indians on the western slopes of the Rockies. And from there it swept down the Columbia to arrive at the Chinook villages in 1775.

The first documented pandemic swept north from Guatemala in the late 1770’s. By 1780 it had reached the Navaho pueblos in New Mexico. From there it moved on to the Comanches who traded with their linguistic cousins the Shoshones and Crows. The Shoshones’ traditional territory bridged the Rockies where they traded both with the Blackfeet on the Plains and with the Kootenai and Piegan Indians on the western slopes of the Rockies. And from there it swept down the Columbia to arrive at the Chinook villages in 1775.

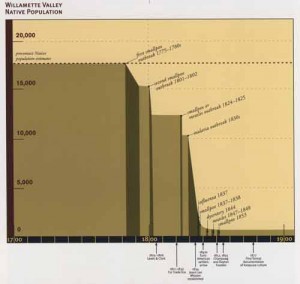

What’s significant about this new information is that the major destruction of the native populations occurred before the arrival of Europeans in the Pacific Northwest. Even before Gray crossed the Columbia bar the region had already been devastated by at least two smallpox scourges that killed almost 20% of the population. Lewis and Clark also noted evidence that an epidemic had passed through the area about 30 years before their arrival. But from 1825 until the time the first wagon trains arrived in 1843, over 90% of the Indians living in the Willamette Valley perished as a result of successive waves of disease sweeping though the Northwest.

In an absolutely haunting incident in 1871, a Flathead Indian responded to a fur trader’s query about a village, by informing him that not only had the entire village perished, but everyone that had ever been there was dead. Old Simon was quoted as saying that “of them remained not even a name” of the place!

In an absolutely haunting incident in 1871, a Flathead Indian responded to a fur trader’s query about a village, by informing him that not only had the entire village perished, but everyone that had ever been there was dead. Old Simon was quoted as saying that “of them remained not even a name” of the place!

Smallpox was most contagious during the first week, but it could still infect others as long as the scabs hung on – which was typically a month. The infection could be conveyed by breathing on others, by touching an infected person, or touching contaminated materials including clothes and blankets. Corpses were contagious for as long as 3 weeks, and the clothes they wore could transmit the disease for as long as one year. By the time that settlers began to arrive in this area the tribes had been decimated. Many of the bands fell apart leaving their ancestral lands, sometimes moving in with the remnants of other tattered tribes. Trade and transportation routes collapsed. Local languages began to disappear as Chinook trade jargon and English began to replace the older languages. The renowned scholar, Henry Dobyens, that has done the greatest amount of work on establishing the actual population levels prior to contact, has estimated that in the first 130 years after contact more than 95% of the native peoples in the Americas perished.

It has happened, and right here in our midst!