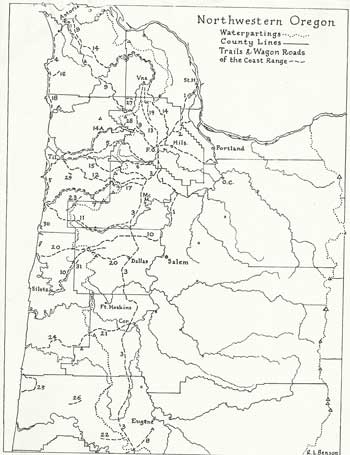

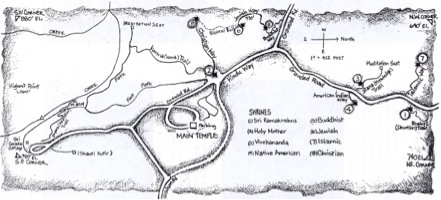

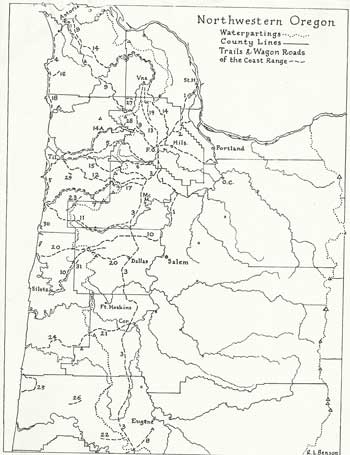

Although I have been collecting materials about early Oregon coastal trails and paths for many years, I was pleasantly surprised to find some original historical research compiled by Robert Benson in 1981. It included this unusual map and this uniquely expansive list of significant trails.

I have presented this map and the associated list with as few editorial (italicized) additions as possible. I can’t say I know more than a handful of these putative trails, but nonetheless I publish them here in part to preserve the record, but also to see if I can conjure some of you out there to respond if you have something interesting to add to the record. Maybe we can coin a new term and call it “crowd researching”.

Here’s Robert’s nicely drawn map:

And here is his list of the various trails:

Indian Trails:

1. Jason Lee Trail, used by missionary searching for a location for his mission.

2. Logie Trail, Fort William Bend on Sauvie Island to Glencoe.

3. Klickitat raiding trail, perhaps same as fur traders’ main Westside route.

4. Ecola Trail, used by Captain Clark’s party going to see whale at Cannon Beach.

5. Pafaan Trail, from Patton Valley via S.Saddle Mtn and Hembree ridge.

6. Tualatins’ steelhead trail to Trask headwaters (from Trail Street in Gaston?)

7. Nenamusa Trail, rumored in use by Tillamooks for vacations and honeymoons.

Explorer’s Trail:

8. Dr. Elijah White’s route from Spencer Butte to ocean via Siuslaw River.

Military Routes:

9. Astoria-Plains Military Road, scouted by Lt. Geo. H. Derby in 1855

10. Doak’s ferry Road, by which cannons reached Siltz (or Forts Yamhill, Hoskins?)

Settler’s Routes:

11. Cattle trail, over which herds were driven to Tillamook and Clatsop farmland.

12. Harris Trail, gave Tillamook access to civilization in all weathers.

13. Cape Horn Wagon Road, west of West Dairy Creek and on to Vernonia.

14. Washington County, Nehalen & Astoria Wagon Road of 1873

14a. Wilson River Stage Road, Gale’s Creek (Gale’s City) to Tillamook.

15. Trask Toll Road, North Yamhill to Tillamook via Fairdale Mineral Springs.

16. Elk Creek Toll road, Cannon Beach to Necanicum River.

Major Hiking Routes, now usable at least in part (in 1981, when this list was compiled)

17. Big Nestucca logging road, unsafe but favored by bicyclists and hikers to the coast.

18. Oregon Coast Trail, planned throughout; officially open at the north end (much more since this was published).

19. Linear trail, on defunct United Railway grade; held up by local opposition.

20 Dallas – Coast Trail, planned along old logging roads; possible for equestrians.

21. Corvallis-Coast Trail, mostly for hikers only, in part for bicyclists too.

22. Eugene – Coast Trail, begun by Boy Scouts; frustrated 10 miles out.

Long Trails Planned, or in use in the 4 major proposed wildernesses.

23. Mt. Hebo Trail, planned to join the Three Rivers and Central Nestucca.

24. Drift Creek Trail, behind Waldport, planned as part of 21 above.

25. Coast Creeks Trail complex, gives views of unique coastal wilderness.

26. Windy Peak Trail in small wilderness between Deadwood and Lake Creeks.

Short but outstanding Scenic Trails:

27. Wolf Creek Falls Trail, with possible extension along Highway 26.

28. Low Divide Trail, joining gale’s Creek Forest camp with Wilson River Stage Road.

29. Munson Creek Falls Trail, through sub-tropical rain forest.

30. Hart Cape Trail, steep but scenic, just north of Cascade Head.

31. Valley of the Giants Trail, access to grove of near champion Douglas Firs.

32. Sutton Creek trail, with a special viewpoint for the handicapped.

I would like to add other trails like those connecting the Tuality plain with Willamette Falls, those trails along the Gorge that bypassed the treacherous rapids, trails along the Nehalem River, the Salmonberry River trail and the traditional crossing routes for the Cascades in Oregon and Washington. But I will leave this entry as un-embellished as possible.

Instead of offering my commentary, I invite you, dear reader, to add your observations! Please comment if you have updates on any of these routes. I also have updated information, but will offer it up elsewhere as we gradually refresh the details of the trails mentioned therein.

Jim