In 1938, Oregon became the largest supplier of timber in the country. By that time demand for timber was once again on the rise, fueled by the wartime demand for construction materials. In the boom and bust cycles that so often characterize extractive industries, Oregon was once again riding a boom in demand, and a consequent increase in cutting and production.

The Invasion of the Night School Loggers:

By the mid-1940’s thoughtful leaders were voicing concerns about the accelerated cutting that was quickly consuming the vast private and public timber stands in Oregon and Washington. Halfway through the war, Lyle Watts, the chief of the Forest Service called for regulation “to stop destructive cutting”. He estimated that as much as 10% of the country’s timber supply was coming from the public forests. If this trend continued, he worried that foresters would soon “exceed sustained-yield cutting budgets.”

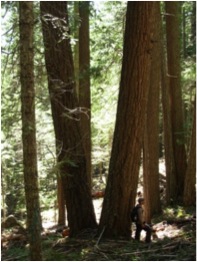

To the contemporary reader it may seem obvious that at some point the amount of timber extracted can exceed nature’s ability to replenish it. In theory, there is a mathematical inflexion point where the value extracted from the forest ecosystems can cover their cost of effective management – in perpetuity. Extract more, and the forest ecosystems suffer. Exploit the forest and its communities too heavily and risk heavier long-term costs, more waste, volatility, lessened safety and possibly disaster.

On the other hand, take a more expansive view of what constitute legitimate “external costs” and it becomes clear that the underlying regenerative aspects of the forest need to be conserved and nurtured. No doubt we will discuss long into the night how these eco-system benefits should be distributed, but most important is that we recognize the broader benefits provided by forest eco-systems to carbon sequestration, tourism, water quality, biodiversity, availability of fish, recreation, hunting and timber. I would like to believe that thoughtful planners have recognized that the multi-faceted forest benefits require proportional investment to preserve and enhance. One of the most important aspects of such an approach is the concept of a sustainable harvest level.

Lyle Watt’s adoption of “sustained-yield cutting budgets” was not the first effort to adopt these “scientific” metrics to forestry. As early as 1934, C.J. Buck, a regional forester in Forest Service Region 6 urged the Northwestern states to adopt sustained-yield management policies. He singled out Clatsop County as an example “cut-out and get-out” logging practices that increased the effect of the boom and bust cycle on families and communities. These voices calling for sustainable forestry weren’t just coming from administrators, and editorial boards. David Mason, a Portland forester closely associated with the lumber trade association developed the most coherent sustained-yield proposal in hopes of stabilizing cutting schedules that were driving down timber prices.

But not all were in accord with this idea. Joseph Kinsey Howard, a progressive journalist from Montana saw all this effort to protect the interests of “the greatest number in the long run” as anti-competitive and an effort to restrain free enterprise. He clearly identified that the depression-era version of sustainability was focused on local sawmills. America, he wrote, was “almost alone among civilized nations” to permit timber owners to harvest as they wished. To restrict private enterprises to use only a few eligible sawmills would inevitably be anti-competitive, he insisted.

Crow’s Pacific Coast Lumber Digest was always good for a juicy quotation. They called the sustained-yield forest management “a sustained grab”, “one more big step” in the direction of “the Russian Plan, wherein crack-pot night-school loggers sent out of Washington will… swarm over our forests and tell our loggers how to cut down their trees.”*

* *Robinson, Landscapes of Conflict, Pg. 15

With the economy heating up public opinion was shifting away from social planning, and Congress was vigorously dismantling strategic New Deal programs, such as the National Resources Planning Board. Increasing wartime demand had so buoyed commodity prices that the idea of controlling harvests suddenly fell out of favor with timber owners. But even as this shift was occurring, policymakers continued to promote the idea of sustainable forestry. Oregon’s Postwar Readjustment and Development Commission maintained that the sustained-yield programs would prevent ghost towns and “abandoned sawmill communities.”**

**Robinson, Landscapes of Conflict, Pg. 150

But the post-war building boom soon silenced discussion of sustained-yield harvests, as the country geared up to produce 15 million housing units over the next ten years. Nonetheless the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the Forest Service continued to try to implement cooperative sustained-yield units, but times were changing dramatically and both agencies moved to increase their allowable cut. As a glut of harvesting began, the private timber operators went on the offensive asking for access roads, better funding for firefighting and insect research and increased harvesting of dead and dying timber.

By 1947 had become the most timber dependent state in the union, with more than 2,000 large wood extraction companies operating throughout the state. The fundamental question of how much wood could be reasonably extracted from the forests was no closer to be answered than it was in the 1930’s.

Decadent Old Growth:

During the immediate post-war period the country sustained a tremendous building boom as the GI’s came home and housing starts began to bulge simultaneously with the arrival of the “boomer” generation. This period was characterized by a technological optimism that touted the “self-evident” benefits of scientific forest management that treated timber like a crop. At the heart of this approach was the notion of sustained-yield forest management, though the implementation of this concept differed markedly on the ground.

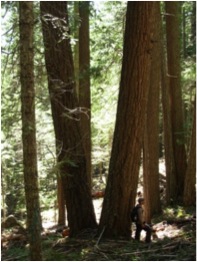

By now Oregon and Washington held 39% of the nation’s standing timber and produced 30% of its timber needs. William Robbins, notes in his excellent environmental history of those time, “Landscapes of Conflict”, that Oregon had become the most timber dependent state in the union by 1947 “with more than 2,000 large and small lumbering and logging operations” with a combined payroll exceeding all other work in the state. H.V. Simpson, the Secretary-Manager of the West Coast Lumber Association (WCLA) averred that Oregon, “once it had been relieved of stagnant old-growth timber” would lead the way into a new era of “orderly cropping of forest products.”* (* Robinson, Landscapes of Conflict, Pg. 35)

Stuart Moir, an officer to several Northwest lumber trade associations suggested that the region become the “nation’s wood lot.” In his optimistic view the removal of trees didn’t represent lost assets, but rather the liberation of valuable space to grow more trees, more efficiently. Forests had to be thinned, protected from natural blight and fire, and harvested according to scientifically deduced schedules that optimized the return based on the trees’ growth rates and prevailing timber prices. This optimization included the “conversion” of “decadent” old-growth forests into faster growing stands of younger trees with harvesting scheduled 80 to 100 years hence

The bullish housing market during the post-war years, especially in California was putting enormous pressure on the timber industry, which was harvesting at unprecedented rates. There was strong pressure to increase the building of access roads. Even the esteemed private colleges of Reed College and Lewis and Clark joined the frenzy by producing a joint report that confirmed the need for more than 14, 475 miles of access roads. Occasionally, I encounter the remnants of tarmac on remote logging roads; this eroding infrastructure dates to that period of aggressive industrial penetration. With few real restraints holding back the allowable cut, the market became the deciding factor in forest management. Market forces could apparently trump scientific management.

The 1970’s: Controversy over spraying the Pacific Northwest timberlands

If you rummage around the Internet like so many of us do, you might stumble across the website for the Alsea Clinic, a modest community health care provider for a remote logging community deep in the Oregon Coastal Forests. Listed among its officers is the secretary: Bonnie Hill. She has served on the board since before the clinic opened and she’s lived in Alsea for 39 years – almost as long as the trees!

Her mention on the board roster states simply that “I, and others who lived in Alsea before the clinic was formed can remember so clearly what it was like to drive over the mountain for every medical need: aching ear infections in crying little children,

injuries that occurred at school in P.E. or athletic events, frequent problems for the elderly, etc.” She was the local high school teacher at the time, and she mobilized the community to establish this remote health center. Nice contribution, end of story? Hardly!

Bonnie may have helped found Alsea Rural Health Care, Inc., but this was the culmination and the spark of a huge political conflagration that ultimately changed logging practices across the entire Pacific Northwest. Nowhere in this modest description does it give Bonnie the credit for exposing one of the most egregious problems literally swirling out from Oregon’s vast logging operations.

In the early seventies, just as I was attending college in Portland, Bonnie was teaching high school in remote Alsea. Being in touch with parents across this forest community she soon became aware of the alarming increase in “miscarriages” across the community. Way before the Internet made such research easily accessible to most people, she began to research the issue and she learned of a study published by James Allen (University of Wisconsin) that linked a similar rise in the early pregnancy loss among rhesus monkey that had been exposed to TCDD, a highly toxic dioxin contained in the 2,4,5-T chemical herbicide used by the timber companies to combat the infamous Tussock moth infestations.

Since the publication in 1962 of Rachel Carson’s hugely influential book, “Silent Spring”, wherein she described the awful and cumulative effects of using DDT, a nationwide struggle was occurring to do away with the use of DDT on foodstuffs, around protected natural areas, and around people. The ban took many years to be applied broadly, and some of the last holdouts were the timber industry who continued to argue that its use in the forest not only necessary to battle the invading Tussock Moth, but that its “ancillary benefits” included helping those people “who might be allergic to the tussock-moth hairs.” As late as 1974, the Forest Service sprayed 421,000 acres in Oregon, Washington and Idaho. But the tide of public opinion was already shifting and despite a 98% “kill rate” for the Tussock moth, opposition began to mount. Evergreen State College Etymologist, Steven Herman called it an “etymological My Lai” – referring to the infamous massacre committed by American troops in Vietnam in 1968.

In response to the overwhelming opposition to DDT that was making its application even for forestry purposes nearly impossible, the Dow Chemical began to develop a civilian use for the highly successful defoliant used across Vietnam, the stuff commonly referred to as “Agent Orange”. Dow Chemical called it Silvex – a compound that included 2,4,5 –T, an herbicide that killed fast-growing hardwoods thus permitting the slower growing Douglas Fir seedling access to the sun. The initial spraying occurred in the early seventies in the Siuslaw National Forest, near Alsea.

Jean Anderson, a clinical psychologist who lived on a cattle ranch adjoining the Siuslaw National Forest was another of the early objectors who began peppering the Forest Service with complaints about the spraying program. She and her husband began to collect scientific information about 2,4,5 – T and were alarmed to realize that emerging scientific information seemed to indicate that the dioxin was one of the most deadly toxins known to man. When she tried to get hold of the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the spraying, she was told that it was too expensive to circulate copies to the community. In 1978, the Forest Service worked with the EPA to review 2,4,5 –T and Silvex, but they simultaneously authorized its use “only after all alternatives had been considered”. Over the next several months howls of protest were met with equally indignant howls from the other side, but the effect was to escalate this issue to the national stage, where the renowned commentator, Jack Anderson latched on to the disturbing evidence of tripled miscarriage rates in Alsea.

Bonnie Hill had not just read James Allen’s early research but she had conducted her own survey of the community’s childbearing mothers. She correlated the information about the time, place and circumstances of these miscarriages against the aerial spraying schedules published by the logging companies. The data showed a high correlation, though Bonnie never claimed a cause-and effect relationship. But by now the EPA was worried. They soon sent a team to visit Alsea, which quickly resulted in a broader survey that covered 1,600 acres across Lincoln and Benton Counties, which confirmed significantly higher miscarriage rates in the study area. With such results the EPA was compelled to issue orders to cease using 2,4,5 – T and Silvex, which contained the same toxin.

Now it was lumber’s turn to voice its outrage, launch a slew of lawsuits and public education campaigns. They also marched out their sympathetic experts “in the weed science and toxicology fields” who claimed the Alsea study was flawed. But when the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the decision, the momentum of the controversy shifted dramatically as the weight of evidence became too preponderant to overcome. The incoming Reagan administration tried briefly to negotiate a settlement with Dow Chemical, but once again newly released data about the virulence of the 2,4,5 –T toxin overwhelmed those secret negotiations and in 1981 Dow Chemical and the EPA ceased any further registrations for 2,4,5 –T.

So, I would respectfully submit that the description of Bonnie Hill’s contribution to her community’s health was much greater than founding a humble community clinic. As this book tries to point out what see you on the surface of the forest and its residents may not be the entire story – and that’s especially true of Bonnie Hill and the modest community of Alsea tucked into the Siuslaw National Forest.

The 1980’s: Endangered Species Act changes NW logging

In the 1980’s America took a step to the right, and habitat protection took a back seat to market principles. Reagan brought with him a cadre of unequivocal opponents of conservation, environmentalism, and habitat protection. James Watt, Reagan’s Secretary of the Interior, was famously hostile to environmental concerns. During his tenure, he set a record for the least species listed under the Endangered Species Act. But such is the nature of a bureaucracy that it tends to blunt the most extreme elements of any administration, regardless of direction.

Reagan’s assistance secretary of agriculture went so far as to delay the implementation of the Northwest land management plans and warn Forest Service planners to de-emphasis protecting wildlife and scenery. Compounding this not-so-benign neglect, Senator Mark Hatfield and Les AuCoin continued to press the Forest Service to support unsustainable levels of cutting on federal timberlands.

Excessive cutting on private timberlands was putting pressure on the public agencies to increase the supply of logs off the federally controlled lands. In 1949 the BLM increased their allowable cut and authorized the construction of more roads. By 1951, the New York Times reported that “More and more lumber operators are looking to national and state-owned forests to piece out their operations.”

Given the feverish demand for increased lumber supplies it is not surprising that both the academic and scientific communities also began to respond to the pressure. University of Oregon professor Louis Hamill suggested shortening the rotational harvest cycle from 100 years to 80 years. Studies produced by the well-respected Portland-based colleges of Lewis and Clark and Reed during this period affirmed the need to build over 14,000 miles of new access roads. At that time Crown Zellerbach estimated that Oregon’s timber stands alone could sustain annual harvests of 8-10 billion board feet for another fifty years. With more intensive forestry management, their forester predicted that the cut could even be increased to 14 billion board feet!

In effect the marketplace and improving production techniques were driving the definition of forest practices, not a concern for the welfare of the forests, or the protection of critical habitat and ecosystem services like clean water, and salmon friendly spawning grounds. Historian Richard Rajala concluded that the timber companies’ focus on profit maximization during this period made it impossible to achieve “a meaningful integration of science and forest law.” His research supported the view that forest research was only permitted to inform public policy if both the corporate and government representatives approved. In a prescient conclusion Rajala asserted that “science needed the sanction of the dominant interests in the political economy” to disrupt the current unsustainable forest practices.

For some time now, fish biologists had been warning over the fragmentation of the old growth forests, and the silting of the salmon spawning grounds by the excessive road building. But when the challenge came it flew in on silent wings from an unexpected quarter.

Under the requirements of the National Forest Management Act the Forest Service was required to identify and protect any “indicator species” that were endangered by industrial uses of the forest. Citing the Endangered Species Act, the Sierra Club brought several suites against the Forest Service in 1987 for not listing the Northern Spotted Owl as an endangered species. This was an important watershed in the national debate about natural resource management and environmental protection. Heretofore, the environmental case had been made almost exclusively on emotional grounds that frequently pitted non-resource based urban communities against those that were dependent upon the forests around them. The introduction of scientific methodology and empirical data to this debate turned the tables on the parties. And the Pacific Northwest lumber interests were soon predicting the demise of the region’s timber industry and warning that the Northwest’s rural communities would be hit by massive reductions in the labor force.

In 1988 Thomas Ward, the well-respected Forest Service biologist was appointed to chair the Interagency Scientific Committee charged with sorting out the conflicting resource management issues. A year later Ward released the Committee’s recommendation that called for establishing Habitat Conservation Areas (HCA’s) across the owls’ established range. In 1991 Federal District Judge William Dwyer issued an injunction barring timber sales on all public lands that included any Spotted Owl habitat. His injunction also accused Presidents Reagan and George H. W. Bush, as well as Mark Hatfield and other Pacific Northwest politicians of increasing the annual harvest so much that it directly contributed to the endangerment of the Northern Spotted Owl.

In 1992 Clinton convened the so-called “Forest Summit” in Portland. The outcome of this most recent confab was the further reduction of the federal timber harvests by 75% from the unsustainable cutting limits of the 1980’s. These reductions led to a decline in Pacific Northwest timber industry employment of 16,695 jobs – way below the 65,000 jobs that the industry sponsored Northwest Forest Research Council had projected.

Finally in 2011, after a long wait the Agriculture department proposed new forest planning rules that had been mandated by the 1976 National Forest Management Act. The rules are intended to guide forest managers decide what areas may be logged, and which should be spared. The fundamental principle guiding the 1976 National Forest Management Act is that the health of the forests and their wildlife are to be valued as highly as the interests of the timber companies. The Clinton administrations wholeheartedly supported this perspective, but the subsequent Bush administrations strove to roll this balance back to favor the commercial interests of the timber and mining companies using public lands.

The Obama administrations newly proposed rules are replete with lofty goals like maintaining “viable” animal populations, but critic claim they are vexingly vague on how to measure the quality of the forest ecosystems and how to ensure that the rules are maintained. So far the Obama administration seems to be trying to finesse the issue with palliatives and smiles. The environmentalists want to see more teeth in their proposals.

The Hidden Culprit: Technology

By the 1960’s mechanization in the logging industry was beginning to have an impact upon employment. Over the previous several decades logging had moved away from the railroad logging, and the use of the “big wheels” used to haul the logs out of the forest. By the 1930’s gasoline powered tractors had taken over the heavy lifting. But the biggest change didn’t come until the 1950’s with the invention of the gasoline powered saw and diesel-powered yarding machines. This triggered a shift away from felling and bucking the trees by hand – an enormous increase in productivity! But that productivity increase came at a price – fewer loggers were needed. By mid-century the logging crews had atrophied to 30% of their original complement.

During the booming 1980’s nearly 200 sawmills had closed and employment in the timber industry had slipped by 25,000 jobs – all due to the increased introduction of technology that permitted increasing volumes of production with ever shrinking numbers of workers.

But of course, this drop in the timber industry employment became a potent argument used by the industry to argue for more logging and increases in the allowable cut on public lands. The loss of jobs they contended was entirely due to the pressures from environmental groups that were stalling progress on implementing timber sales. While litigation did play an important role in redefining the forest management rules in the Pacific Northwest, it would be incorrect to lay the entire blame for the employment decrease in the timber industry at the feet of the environmentalists.

O & C Counties

One of the factors affecting Oregon’s forests is the treatment of the so-called “O & C” county lands. To encourage the building of a rail link between Portland and San Francisco in 1866, the federal government offered a huge reward in the form of a land grant of 3,700,000 acres. This was to be parceled out in checkerboard pattern and was intended to be resold to settlers at $2.50 per acre. But in 1916, most of the land was reconveyed to the federal government and since then 18 counties where the O&C lands are located have received payments from the federal government to compensate for the loss of timber and tax revenues. The final extension of these payments that occurred in 2012 is expected to be the last renewal of the program.

In recent years many of the counties have relied on this source of funds to fund their local governments. However, the legislative mandates that have served as the legal basis for these payments has changed over the years, and the payment amounts have gradually diminished. Currently, the underlying statute that governs these payments is an extension of the Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act of 2000, which was renewed in 2012.

Faced with a gradually diminishing stream of revenues from the O&C lands, several counties in Oregon found themselves unable to fund even the most basic functions of local government, such as policing and jailing criminals. Since these counties cannot declare bankruptcy and yet they must provide county services mandated by the state, some counties have considered merging.

Overall the financial pressure caused many of the affected counties to increase their harvests on the O&C lands to the point that it was devastating the wildlife habitat and led to the eradication of many species over much of the affected forestland.

One of the worst affected counties, Josephine County near the California border, proposed a property tax, which failed to gain voter approval. As a consequence Josephine County had to reduce its staff by 2/3 and release inmates from the county jail because there were no funds to maintain them in jail. The situation was so dire in some counties that in 2012 the Oregon Legislature specifically permitted the counties to divert monies intended for the maintenance of forest roads to be used instead to pay for law enforcement patrols. I guess this goes to show that it really is the “wild west” in some parts of Oregon.

Sources: Robinson, Landscapes of Conflict, Pg. 210, 322-329

Current issues: Landslides and clear-cutting

Landslides are endemic to Oregon, where the high moisture content can turn soil into pudding and turn gentle slopes into torrents of mud and debris. In 1996 landslides killed 5 people in Oregon and caused damage to more than 100 homes in the Portland area. In December of 2007 a landslide swept down from a clear cut west of Clatskanie and nearly buried some buildings and its inhabitants in Woodson. In 1933 four people were killed in the same area by landslides.

In 1997 the Department of Forestry was asked by the Legislature to put an end to logging on very steep slopes. A 1999 study by the department established that many of the landslides on forestlands were linked to debris flows emanating from clear-cut areas. As a result the Department of Forestry has come under increasing pressure to restrict logging on steeper slopes. In 2003 the Department responded with OAR 629-623-000 which defines the forestry practices as they relate to landslides. It defines any slope steeper than 80%, or a draw steeper than 70% as too dangerous to log. But the regulation also contains an escape hatch that permits a geotechnical specialist to determine the slope steepness based on site-specific measures that presumably override the prevailing gradient and thus permit less restrictive logging practices. The intent of the semi-voluntary restrictions is to limit ground disturbances on high-risk sites. When applied, the rules are intended to “prevent local over-steepening and slope gouging by cable yarding.” The rules also require loggers to minimize the buildup of “slash” on the steep slopes below any high-risk sites. The construction of skid trails on high-risk sites was also prohibited.

Past studies had also revealed that most landslide damage on forestlands were attributable to the road systems built to support the logging activities. In addition these studies found that road-associated landslides were typically about four times larger in volume than non-road associated landslides. Of course much of this road-associated damage is invisible to the general public that rarely enters the timberlands to see the effects of washed out roads. But for the industry these costs are not trivial.

After the slides in Woodson splashed into public view to reveal the hidden dangers of clear cutting and road building, pressure began to build on the Department of Forestry to eliminate logging on steep slopes. In response to calls for a moratorium on steep slope logging, but the DoF responded with a additional voluntary measures.

After the slides in Woodson splashed into public view to reveal the hidden dangers of clear cutting and road building, pressure began to build on the Department of Forestry to eliminate logging on steep slopes. In response to calls for a moratorium on steep slope logging, but the DoF responded with a additional voluntary measures.

According to the noted environmental historian William G. Robbins, “logging practices in some parts of the state continue to be problematic, despite the Department of Forestry’s assertions to the contrary. Several people died in landslides brought about by steep slope logging. The Board of Forestry voted to ask loggers to voluntarily restrict steep slope logging. But public pressure pushed the issue before the legislature and the legislature added further restrictions, but the rules applying these additional safeguards have yet to be published.

The other perennial issue that has divided opinions about logging is the highly visible concern over the practice of clear-cutting. This concern was the direct result of the massive increase in timber harvesting that occurred from the 1970’s through the end of the century. During that period public opinion shifted dramatically in response to the highly visible deforestation in such well travelled corridors like the foothills of Mt. Hood, the Coastal Mountains, and the Siskiyou’s. Several books were published during this period that focused exclusively on clear-cutting, including Chris Anderson’s Edge Effects (1993), and the Sierra Club large format publication (1995) entitled, “Clearcut: The Tragedy of Industrial Forestry.”

The industry’s response was (and remains) that some tree species, including the ubiquitous Douglas Fir, are shade intolerant and therefore must be planted en masse. This means that the site must be clear-cut to remove any trees that might crowd out the sunlight and thus stunt the growth of the trees. Foresters insist that the practice of clear-cutting is not just necessary to reduce costs, but is essential to produce a lush new forest. The industry experts claim that the practice replicates the actions of forest fires that “transforms a biological desert” into a highly productive forest that can help watersheds by replacing old growth trees with “higher water yielding younger trees.”

In February 2013 this issue erupted once again. The catalyst was a proposed Forest Service’s timber sale that included 16,215 acres along the western border of Oregon’s only national park. This threat to one of Oregon’s most renowned views quickly galvanized a broad array of opponents that vehemently opposed the cutting of trees 300-400 years old. The logging roads would access forest that had not seen commercial logging for more than 60 years and served as wilderness in one of Oregon’s highest-valued recreation areas. According to Oregon Wild’s website, “the Bybee logging project would log 1,300 acres in the proposed Crater Lake Wilderness. This would effectively cut off several intact wildlife corridors with logging and road building. The project includes 12 miles of new roads…(and) would be enough to fill 7000 log trucks.”

In February 2013 this issue erupted once again. The catalyst was a proposed Forest Service’s timber sale that included 16,215 acres along the western border of Oregon’s only national park. This threat to one of Oregon’s most renowned views quickly galvanized a broad array of opponents that vehemently opposed the cutting of trees 300-400 years old. The logging roads would access forest that had not seen commercial logging for more than 60 years and served as wilderness in one of Oregon’s highest-valued recreation areas. According to Oregon Wild’s website, “the Bybee logging project would log 1,300 acres in the proposed Crater Lake Wilderness. This would effectively cut off several intact wildlife corridors with logging and road building. The project includes 12 miles of new roads…(and) would be enough to fill 7000 log trucks.”

The US Forest Service and industry representatives counter that the proposed timber harvesting activity would be conducted with extraordinary care. Clear-cuts would be limited to three-quarter-acre patches that “would blend with the vegetation in the Crater lake National Park” which already has open patches from wildfires and previous logging activities. The loggers would avoid old growth timber as defined by the Northwest Forest Plan, but environmentalists counter that the thinning objectives stated in the proposal do not distinguish between old growth and younger stands. Both Oregon Wild and Cascadia Wildlands are challenging the Bybee timber sale.

Of particular note in this debate is the introduction of smaller scale clear cutting dimensions. Though this is a great improvement, I suspect that this issue will not disappear since Oregon’s population continues to urbanize and loose its ties to the resource harvesting industries that once dominated public opinion in this region of the country.

Of particular note in this debate is the introduction of smaller scale clear cutting dimensions. Though this is a great improvement, I suspect that this issue will not disappear since Oregon’s population continues to urbanize and loose its ties to the resource harvesting industries that once dominated public opinion in this region of the country.

Sources: Oregonian, Logging Battle Lines drawn near Crater Lake, February 27, 2013