In the middle of winter my explorations seem to slow down partly because of the cold drenching rains, partly due to the family festivities, and further slowed by the seasonal sniffles and colds that make one loath to forsake the comforts of home. But come January and I get that restlessness that eventually causes my wife to send me out into the woods, knowing full well that my demeanor and general grumpiness won’t be dissipated by anything less than letting me slip my leash and disappear into the fog and low hanging clouds that shroud the coastal mountains at this time of year.

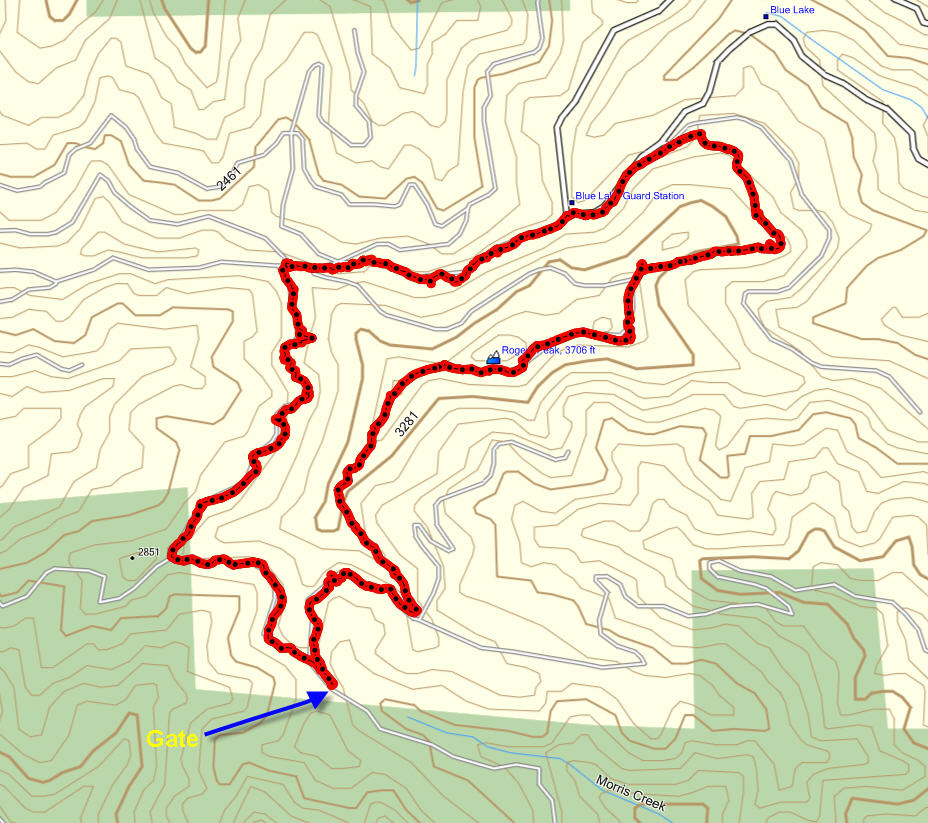

This year the catalyst came after a morning spent interviewing Craig Olsen and Tom Budge , the current and former managers of Longview Fiber’s Vernonia unit. I had asked to meet with them to get a perspective of how they perceive the land through which I have been traipsing for these last few years. After wearing down a half dozen pairs of hiking boots exploring all the remote nooks and crannies of the Longview Fiber logging road network, I was particularly interested in knowing more about how these dusty filaments of industry had been laid and maintained along the ever shifting Coast range slopes.

This year the catalyst came after a morning spent interviewing Craig Olsen and Tom Budge , the current and former managers of Longview Fiber’s Vernonia unit. I had asked to meet with them to get a perspective of how they perceive the land through which I have been traipsing for these last few years. After wearing down a half dozen pairs of hiking boots exploring all the remote nooks and crannies of the Longview Fiber logging road network, I was particularly interested in knowing more about how these dusty filaments of industry had been laid and maintained along the ever shifting Coast range slopes.

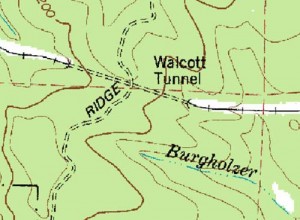

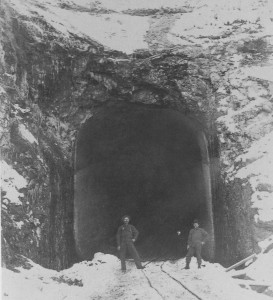

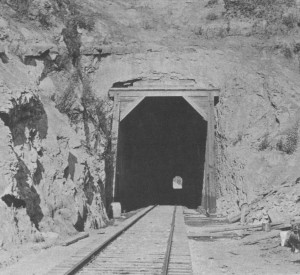

Tom Budge recounted how he was the first Longview Fibre employee to move to the Vernonia unit in 1962. The biggest challenge they had faced in those days had been harvesting the huge dead-fall that resulted from that year’s Columbus Day Storm.  In those days there were few roads through the area. Mostly they had access via the railroad grades that had been vacated of tracks and some CCC roads. The latter were designed for fire protection and not wood extraction.

In those days there were few roads through the area. Mostly they had access via the railroad grades that had been vacated of tracks and some CCC roads. The latter were designed for fire protection and not wood extraction.

Building roads in Columbia County was a bit easier than in Clatsop or Tillamook counties, because the terrain was not as treacherous. Longview Fibre was able to build about 20 miles of road a year. In the denser and steeper terrain near the coast they were only able to construct about 7 miles of roads per year. While this may not seem like a huge accomplishment, until you consider the plight of Lieutenant George H. Derby who was charged with surveying an overland route from Astoria to Salem in 1865. In his report on the proposed Military Road, Lieutenant Derby wrote thatin order to, “get through (the underbrush) with our pack animals, laboring incessantly from daylight until almost dark, with six active axemen, (they were) seldom making more than 5 miles a day” to simply cut an initial footpath through the wild terrain.

With the building of the roads came increased access to the forests and eventually it became necessary to install gates to combat the increasing timber theft, vandalism and trash deposits. This new exclusion caused an acrimonious rift with the local communities who had been hunting these lands for generations and felt it was their “God Given” right to access the forests.

acrimonious rift with the local communities who had been hunting these lands for generations and felt it was their “God Given” right to access the forests.

Asked about whether an entry fee similar to the one imposed by International Paper in Southern Oregon might eventually be imposed on Longview Fibre properties in northern Oregon, both Tom and Craig grimaced remembering the fight they had when the “blue gates” were erected. No, they needed the goodwill of the communities they operated in and they didn’t feel that it would be possible to impose entry fees in Northern Oregon where hunting by the locals (on private timber lands) was an essential means of keeping their larders stocked over the winter.

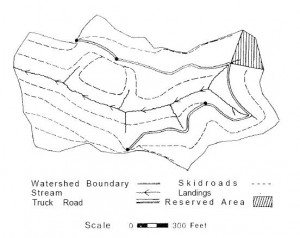

When I asked how these roads were built Tom rummaged through an old bookshelf and extracted a copy of a 1997 typewritten “Treatise on Logging Road Layout and Related Subjects” by “Bull” Durham. As I was to discover the related subjects were the real gems in this “treatise”. The treatise starts with the following practical advice, “After the office interview (with the land owner) have the client take you to the property and show you what he knows: roads, line crossings, line tags, mean dogs, crazy hermits, hostile widows.”

Yes, I did finally learn that the “gradeline” roads were so designated because of the way they were surveyed – using an elevated line at the height of your eye and marked along the tree-line. These gradeline roads usually connected to the “mainlines” which were the main arterial routes providing access to vast tracts of timber. Road grades for logging roads, Bull advised, should be limited to 15% (a rise of 15 feet over a total distance of 100 feet).

At grades higher than 15% it becomes difficult to “ballast” or maintain a rocked surface…18% was considered the absolute maximum.In sharp curves the forest often had to be cut back to keep the long logs jutting off the end of the load from gouging the embankments on the outside of the curve. Cars travelling in the opposite direction who had the misfortune to meet a log truck in such a corner had, on occasion, been swept off the road and tumbled down the mountainside. The cautionary tales about driving on active logging roads are not entirely frivolous…

But the life of a road builder was not just about trigonometry tables, steel tapes and staff compasses. Bull Durham makes sure to warn us about the many sources of danger in the woods, including the usual litany of hazards from bear to buck deer in mating season (“they go a little goofy”) and even mushroom hunters! He also warns against hunters (homo stupidus) suggesting that they “may shoot at anything; they go a little nuts during the hunting season. Don’t wear bright colors to give them a target.”

But the life of a road builder was not just about trigonometry tables, steel tapes and staff compasses. Bull Durham makes sure to warn us about the many sources of danger in the woods, including the usual litany of hazards from bear to buck deer in mating season (“they go a little goofy”) and even mushroom hunters! He also warns against hunters (homo stupidus) suggesting that they “may shoot at anything; they go a little nuts during the hunting season. Don’t wear bright colors to give them a target.”

But his final warning about salamanders was truly bizarre, “Several years ago in Coos County the rigging crew on a yarding job were setting the chokers down in a draw where they turned up a giant salamander…some of the boys dared another one to bite the head off the salamander…the boy took the dare; bit the head off and went into convulsions and died before anything could be done for him.“

But his final warning about salamanders was truly bizarre, “Several years ago in Coos County the rigging crew on a yarding job were setting the chokers down in a draw where they turned up a giant salamander…some of the boys dared another one to bite the head off the salamander…the boy took the dare; bit the head off and went into convulsions and died before anything could be done for him.“