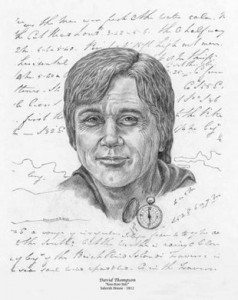

The shadowy fog wreathed London in that gloomy winter of 1783. Its chill dank air permeated into the austere schoolroom and gripped at the hearts of the two boys that stood stiffly before the visiting Secretary of the renowned Hudson Bay Company. The oldest boy, Samuel John McPherson was apprehensive. He knew that the school’s board of governors was anxious to seek apprenticeships for its older boys so that the school could accommodate more children whose lack of education might otherwise doom them to a dismal future in Dickensian England. Alongside him stood David Thompson, a shy welsh boy, whose arrival at the school had been precipitated by the untimely death of his father shortly after the family’s arrival in London.

The shadowy fog wreathed London in that gloomy winter of 1783. Its chill dank air permeated into the austere schoolroom and gripped at the hearts of the two boys that stood stiffly before the visiting Secretary of the renowned Hudson Bay Company. The oldest boy, Samuel John McPherson was apprehensive. He knew that the school’s board of governors was anxious to seek apprenticeships for its older boys so that the school could accommodate more children whose lack of education might otherwise doom them to a dismal future in Dickensian England. Alongside him stood David Thompson, a shy welsh boy, whose arrival at the school had been precipitated by the untimely death of his father shortly after the family’s arrival in London.

Standing before them that morning was the austere Secretary of the Hudson Bay Company who inspected them, while explaining to the school master that the Hudson Bay Company maintained trading stations throughout the wilds of North America from whence they extracted a fortune in beaver pelts. Frowning sternly, he explained, it was not enough to employ the sturdy Orkney and Hebrides men that navigated their canoes up the wild rivers of the north. To run this business, the Hudson Bay Company needed clerks to record and manage the trade – currently they were in dire need of new clerks! Not wishing to snub a benefactor, the school quickly nominated both Samuel and David, and they were told to prepare for their imminent depart from England and all that they had ever known. Samuel immediately fled and disappeared into the murk of history, but the following May David Thompson bade farewell to his mother and remaining siblings and boarded the Prince Rupert for the passage to Churchill, the HBC’s main base on the western shore of Hudson’s Bay.

Samuel immediately fled and disappeared into the murk of history, but the following May David Thompson bade farewell to his mother and remaining siblings and boarded the Prince Rupert for the passage to Churchill, the HBC’s main base on the western shore of Hudson’s Bay.

Arriving in early September the Prince Rupert took on its cargo of canvas wrapped fur bales and soon prepared to return to England. Many years later David recalled the sense of isolation that he felt as he stood on a pile of barren rock and watched the ship that was his only link to all that had been familiar recede into the distance, “While the ship remained at anchor, (the separation) from my parents and friends appeared only a few weeks distance, but when the ship sailed …the distance became immeasurable and I bid farewell to my country, an exile for ever.”

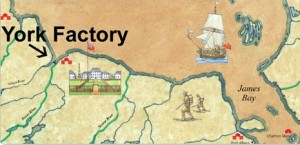

The boy would spend the next year learning the fur trade behind a 12’ stockade that enclosed a weather-beaten cluster of unpainted huts perched on the banks of the cold and muddy Churchill River, just above where it flowed into Hudson’s Bay. In September 1785, he was transferred to York Factory situated near the mouths of the Nelson and Hayes Rivers – a six-day journey from Churchill. Aside from these two posts located near the navigable Hudson Bay, the Hudson Bay company had recently established three trading posts further inland: Cumberland

The boy would spend the next year learning the fur trade behind a 12’ stockade that enclosed a weather-beaten cluster of unpainted huts perched on the banks of the cold and muddy Churchill River, just above where it flowed into Hudson’s Bay. In September 1785, he was transferred to York Factory situated near the mouths of the Nelson and Hayes Rivers – a six-day journey from Churchill. Aside from these two posts located near the navigable Hudson Bay, the Hudson Bay company had recently established three trading posts further inland: Cumberland  House, Hudson House and Manchester House situated along the Saskatchewan River. These outposts were designed to counter the competition that the company was experiencing from the French Canadians who ignored the HBC’s exclusive trading rights throughout the vast northern interior. It was this encroachment by the French Canadian voyageurs that launched David on his epic explorations westwards when he agreed help establish a new inland trading post located 67 days westwards by canoe – just beyond HBC’s westernmost outpost at Cumberland House. During his sojourn in Cumberland House, where he was convalescin

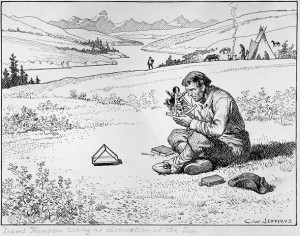

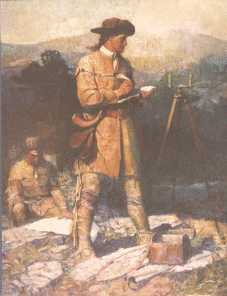

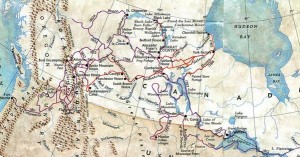

House, Hudson House and Manchester House situated along the Saskatchewan River. These outposts were designed to counter the competition that the company was experiencing from the French Canadians who ignored the HBC’s exclusive trading rights throughout the vast northern interior. It was this encroachment by the French Canadian voyageurs that launched David on his epic explorations westwards when he agreed help establish a new inland trading post located 67 days westwards by canoe – just beyond HBC’s westernmost outpost at Cumberland House. During his sojourn in Cumberland House, where he was convalescin g from a badly broken leg, Thompson was introduced to the craft of practical astronomy. Over time, he became adept at this celestial method for determining both longitude and latitude so that he was able to make reasonably accurate maps of his explorations. In 1797 it was these skills that brought Thompson to the attention of the Montreal-based North West Company, who promptly hired him to survey their trading routes.

g from a badly broken leg, Thompson was introduced to the craft of practical astronomy. Over time, he became adept at this celestial method for determining both longitude and latitude so that he was able to make reasonably accurate maps of his explorations. In 1797 it was these skills that brought Thompson to the attention of the Montreal-based North West Company, who promptly hired him to survey their trading routes.

Ever since the French-Canadian explorer, Peter Pond had opened the way westwards for the voyageurs in 1778-1779 with the opening of a canoe route over the continental divide, the race had been on for their competitors, the Hudson Bay Company and the Northwest Company to find competing routes into the western portions of the continent. In 1789, William McKenzie began searching for the fabled Columbia River, but ended up on the Artic Ocean instead. In 1792 he tried again and this time he discovered a mighty westward flowing torrent that the Indians called the Tacouthe Tesse, but he was unable to follow it due to impenetrable terrain. In 1792, Captain Gray finally penetrated the violent Columbia bar finally establishing that this massive river was navigable deep into the continent. In 1804 the Northwest Company decided to send Simon Fraser to reconnoiter McKenzie’s Tacouthe Tesse – to see whether

Company to find competing routes into the western portions of the continent. In 1789, William McKenzie began searching for the fabled Columbia River, but ended up on the Artic Ocean instead. In 1792 he tried again and this time he discovered a mighty westward flowing torrent that the Indians called the Tacouthe Tesse, but he was unable to follow it due to impenetrable terrain. In 1792, Captain Gray finally penetrated the violent Columbia bar finally establishing that this massive river was navigable deep into the continent. In 1804 the Northwest Company decided to send Simon Fraser to reconnoiter McKenzie’s Tacouthe Tesse – to see whether it was the source of the Columbia River. This tumultuous stream, later renamed the Frazer River, proved impossible to navigate and difficult in the extreme to even follow on foot. In 1805, the Lewis and Clark expedition traveled the lower reaches of Columbia River and confirmed that it was navigable nearly all the way to the Rockies. Finally, in 1809 John Jacob Astor began negotiations with the Northwest Company about possibly collaborating to open the fur trading routes in the far west – not to gather the pelts for the European market, but instead to ship them to China. The negotiation eventually foundered, but tha

it was the source of the Columbia River. This tumultuous stream, later renamed the Frazer River, proved impossible to navigate and difficult in the extreme to even follow on foot. In 1805, the Lewis and Clark expedition traveled the lower reaches of Columbia River and confirmed that it was navigable nearly all the way to the Rockies. Finally, in 1809 John Jacob Astor began negotiations with the Northwest Company about possibly collaborating to open the fur trading routes in the far west – not to gather the pelts for the European market, but instead to ship them to China. The negotiation eventually foundered, but tha t did not keep Astor from sending his own overland team to the Columbia River where they were supposed to link up with the Tonquin, which set sail in the fall of 1810. There they planned to establish the first American outpost and secure the Columbia River for the American traders.

t did not keep Astor from sending his own overland team to the Columbia River where they were supposed to link up with the Tonquin, which set sail in the fall of 1810. There they planned to establish the first American outpost and secure the Columbia River for the American traders.

And so it should not have come as a surprise to Thompson that his employers, the Northwest Company now felt some urgency about laying a credible claim to the Columbia River. But David Thompson was taken unawares when he received instructions in 1810 seek the headwaters of the Columbia by means of ascending the Saskatchewan River. At the age of 40 years he had thought it time forsake the fur trade to which he had already devoted 27 years of his life, living under extremely primitive and dangerous circumstances. He had planned to travel back to Montreal and settle there with his family. But when the summons arrived to organize this final expedition, Thompson realized that it represented the capstone of all his prior efforts and agreed to lead this final effort to locate the headwaters of the Columbia River.

And so it should not have come as a surprise to Thompson that his employers, the Northwest Company now felt some urgency about laying a credible claim to the Columbia River. But David Thompson was taken unawares when he received instructions in 1810 seek the headwaters of the Columbia by means of ascending the Saskatchewan River. At the age of 40 years he had thought it time forsake the fur trade to which he had already devoted 27 years of his life, living under extremely primitive and dangerous circumstances. He had planned to travel back to Montreal and settle there with his family. But when the summons arrived to organize this final expedition, Thompson realized that it represented the capstone of all his prior efforts and agreed to lead this final effort to locate the headwaters of the Columbia River.

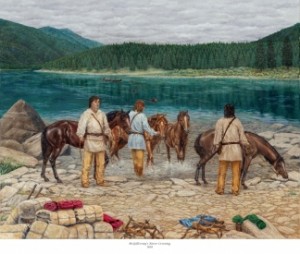

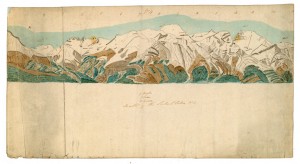

In a mere days he assembled his expedition comprised of six canoes, twenty-four men and six thousand pounds of trade goods. They traveled up the Saskatchewan River, but blocked by aggressive Piegan Indians, the group struck north on an old Assiniboine trail taking a month to cover the 110 miles to the Athabasca River. Now, just fifty miles from the mountains they camped for nearly four weeks while they built sleds and crafted snowshoes to help make a dangerous  mid-winter crossing of the Rockies in temperatures that dipped daily to minus 30 degrees or more. On the 29th of December 1810, twelve expedition members clothed in woolens and leather outer garments and accompanied by eight dog sleds and four packhorses began the long climb through the deep snow into the huge fastness of the continental divide.

mid-winter crossing of the Rockies in temperatures that dipped daily to minus 30 degrees or more. On the 29th of December 1810, twelve expedition members clothed in woolens and leather outer garments and accompanied by eight dog sleds and four packhorses began the long climb through the deep snow into the huge fastness of the continental divide.

Several of the French Canadians in the group were soon spooked by the vast expanse of huge looming mountains that dwarfed their puny presence. They became convinced that mammoths roamed these snowy valleys and would soon gore them with their huge curved tusks. With the greatest  difficulty and urgent persuasion, Thompson was able to keep his group together until they descended the western slopes to the banks of the Columbia. But once there the recalcitrant French Canadians once again refused to proceed, and announced that they would turn back. Left with only three companions Thompson was wise enough not to proceed onwards through the territory of Indian nations that had probably never have seen a white man before. So he turned northwards to resupply at several outposts that he had previously directed to be built near present-day Kalispell and Spokane.

difficulty and urgent persuasion, Thompson was able to keep his group together until they descended the western slopes to the banks of the Columbia. But once there the recalcitrant French Canadians once again refused to proceed, and announced that they would turn back. Left with only three companions Thompson was wise enough not to proceed onwards through the territory of Indian nations that had probably never have seen a white man before. So he turned northwards to resupply at several outposts that he had previously directed to be built near present-day Kalispell and Spokane.

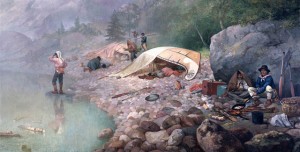

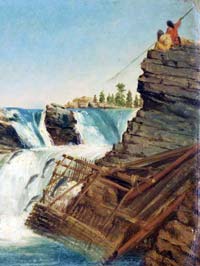

After resupplying and recruiting more reliable companions, he resumed the southward journey with five remaining French Canadians, two Iroquois, and two Salish speaking interpreters. From Spokane House they traveled northwest to the  Columbia River, where they encountered nearly a thousand Indians gathered for the fishing at Kettle Falls. Here they build a cedar canoe and on July 2nd, they resumed their epic exploration, “to explore this river in order to open out a passage for the Interior trade with the Pacific Ocean”. Although Lewis and Clark had traveled and surveyed the lower Columbia River, the portion of the river ahead of them was now completely unknown to any European travellers. By surveying this unknown stretch of the river and proceeding to the mouth of the river, Thompson would soon become the first explorer to travel the entire length of the Columbia River.

Columbia River, where they encountered nearly a thousand Indians gathered for the fishing at Kettle Falls. Here they build a cedar canoe and on July 2nd, they resumed their epic exploration, “to explore this river in order to open out a passage for the Interior trade with the Pacific Ocean”. Although Lewis and Clark had traveled and surveyed the lower Columbia River, the portion of the river ahead of them was now completely unknown to any European travellers. By surveying this unknown stretch of the river and proceeding to the mouth of the river, Thompson would soon become the first explorer to travel the entire length of the Columbia River.

From here on out their travel was accelerated by the pace of the river they were following. Along the way they visited with numerous tribes to learn about the local circumstances and to trade for food. Leaving the territory of the Salish speakers, they were now swept southwards for one hundred and forty miles through a high arid plateau. The Indians they encountered on this desolate stretch of the river lived on roots, berries and salmon and were, according to Thompson, “too impoverished to wage war”. In early July they arrived at the confluence with the Snake River, where the river made a huge turn and began its final journey to the coast and into the Pacific Ocean. From here on they began encountering signs of prior contact such as spotting the bronze medallions handed out by Meriwether Lewis six years prior. Indeed, from here on they soon began to encounter Indians with increasing frequency camped along the river’s shores harvesting the fall salmon runs.

From here on out their travel was accelerated by the pace of the river they were following. Along the way they visited with numerous tribes to learn about the local circumstances and to trade for food. Leaving the territory of the Salish speakers, they were now swept southwards for one hundred and forty miles through a high arid plateau. The Indians they encountered on this desolate stretch of the river lived on roots, berries and salmon and were, according to Thompson, “too impoverished to wage war”. In early July they arrived at the confluence with the Snake River, where the river made a huge turn and began its final journey to the coast and into the Pacific Ocean. From here on they began encountering signs of prior contact such as spotting the bronze medallions handed out by Meriwether Lewis six years prior. Indeed, from here on they soon began to encounter Indians with increasing frequency camped along the river’s shores harvesting the fall salmon runs.

As the river gathered force they were swept downstream on the powerfu l currents that roiled the river, surging into massive rapids as it was forced through narrow constrictions, and increasingly hemmed in by towering black cliffs. Thompson wrote that, “imagination can hardly form an idea of the working of this immense body of water under such compression, raging and hissing as if it were alive”. But once through this massive portal, Thompson and his men were astounded to see the countryside turn into verdant forested mountains with fantastic waterfalls cascading into the River. Even the Indians were different here. Not only were they shorter and stockier, but they also seemed to eschew any clothing whatsoever! And they spoke a language unknown to Thompson and his Salish-speaking interpreters.

l currents that roiled the river, surging into massive rapids as it was forced through narrow constrictions, and increasingly hemmed in by towering black cliffs. Thompson wrote that, “imagination can hardly form an idea of the working of this immense body of water under such compression, raging and hissing as if it were alive”. But once through this massive portal, Thompson and his men were astounded to see the countryside turn into verdant forested mountains with fantastic waterfalls cascading into the River. Even the Indians were different here. Not only were they shorter and stockier, but they also seemed to eschew any clothing whatsoever! And they spoke a language unknown to Thompson and his Salish-speaking interpreters.

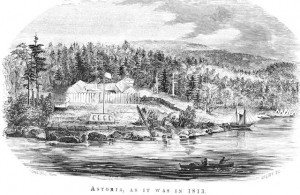

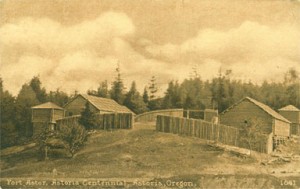

Finally, on July 15 the group approached the mouth of the river. Here they took time to tidy themselves up before approaching the settlement that Astor’s men  had established only months previously. A few miles onwards they finally spotted their destination – a small clutch of huts clustered together in a small clearing and surrounded by gigantic forests that dwarfed their presence and almost ridiculed the tiny fluttering flag that few above the settlement. This was the Americans’ first settlement in Oregon only 4 months after it had been carved from the primordial jungle!

had established only months previously. A few miles onwards they finally spotted their destination – a small clutch of huts clustered together in a small clearing and surrounded by gigantic forests that dwarfed their presence and almost ridiculed the tiny fluttering flag that few above the settlement. This was the Americans’ first settlement in Oregon only 4 months after it had been carved from the primordial jungle!

Needless to say, the Americans were quite surprised to receive such visitors. They had themselves been preparing to launch an expedition to go upriver when they spotted the large canoe rounding Tongue Point.  As it approached a British flag was spotted fluttering from the stern. In the boat were several gaily attired voyageurs and at the rear a neatly dressed man that appeared to be their leader. Landing at the community’s newly built wharf, the leader sprang out and without hesitation announced himself as David Thompson, a partner in the North West Company.

As it approached a British flag was spotted fluttering from the stern. In the boat were several gaily attired voyageurs and at the rear a neatly dressed man that appeared to be their leader. Landing at the community’s newly built wharf, the leader sprang out and without hesitation announced himself as David Thompson, a partner in the North West Company.

The group was heartily welcomed and feted all around. While the arrival of this arrival of a British contingent on the western shores of the continent occasioned much conviviality, the strategic message was not lost upon its participants. The arrival of representatives from one of the most successful trading conglomerates could only portend increased competition for the natural resources the American hoped to secure. And history would soon prove those that understood these strategic dimension correct. Within a few years the Hudson Bay Company would dominate trade on the Lower Columbia and Astoria itself would soon change hands and the flag rippling in the coastal breeze would soon sport a Union Jack.

The group was heartily welcomed and feted all around. While the arrival of this arrival of a British contingent on the western shores of the continent occasioned much conviviality, the strategic message was not lost upon its participants. The arrival of representatives from one of the most successful trading conglomerates could only portend increased competition for the natural resources the American hoped to secure. And history would soon prove those that understood these strategic dimension correct. Within a few years the Hudson Bay Company would dominate trade on the Lower Columbia and Astoria itself would soon change hands and the flag rippling in the coastal breeze would soon sport a Union Jack.

We don’t know exactly what was said at this historic meeting on the sunny shores of the Columbia, but if only we could remind David Thompson how far he had come, both literally and figuratively, from that dank December day nearly 28 years ago when his destiny was peremptorily altered. Since then he had been transformed from a shy Welsh youth, to one of the world’s foremost explorers, and now the first man to navigate the mighty Columbia from its source to the Pacific Ocean. Not only had he traveled from Europe into the wilds of North America, but he had also explored more than fifty thousand miles of rivers and trade routes extending across the entire North American continent. It seemed, at that moment, as if his name had been writ large into the great book of accomplishments.

We don’t know exactly what was said at this historic meeting on the sunny shores of the Columbia, but if only we could remind David Thompson how far he had come, both literally and figuratively, from that dank December day nearly 28 years ago when his destiny was peremptorily altered. Since then he had been transformed from a shy Welsh youth, to one of the world’s foremost explorers, and now the first man to navigate the mighty Columbia from its source to the Pacific Ocean. Not only had he traveled from Europe into the wilds of North America, but he had also explored more than fifty thousand miles of rivers and trade routes extending across the entire North American continent. It seemed, at that moment, as if his name had been writ large into the great book of accomplishments.

Much would change in the Pacific Northwest over the coming decades and the capricious memory that we call history would exalt some while overlooking others. The accomplishments of Lewis and Clark would come to rank among the nation’s highest achievements. Na mes like Simon Frazer and Alexander Mackenzie provided the superlative adornments to Canada’s exploratory history, but David Thompson was destined to eventually die penniless and unknown long after his retirement in Terrebonne, a village on the outskirts of Montreal. It has only been in the last few years that his incredible achievements have been resurrected by in such worthwhile historical accounts as D’Arcy Jenish’s book The Epic Wanderer, and Jack Nisbet’s The Mapmaker’s Eye.

mes like Simon Frazer and Alexander Mackenzie provided the superlative adornments to Canada’s exploratory history, but David Thompson was destined to eventually die penniless and unknown long after his retirement in Terrebonne, a village on the outskirts of Montreal. It has only been in the last few years that his incredible achievements have been resurrected by in such worthwhile historical accounts as D’Arcy Jenish’s book The Epic Wanderer, and Jack Nisbet’s The Mapmaker’s Eye.

But for those of us that live along the Columbia River, we should add this scrappy Welshman to our pantheon of explorers for not simply completing the first source-to-mouth navigation of  the Columbia River, but also for the over fifty thousand miles of exploration that he accomplished over his 28 years of wandering through the northwestern regions of this continent. As one who himself has undertaken just a minuscule scope of exploring the watersheds of Northwestern Oregon, David Thompson stands out as a shining example of diligence, perseverance and intelligent observation along the way.

the Columbia River, but also for the over fifty thousand miles of exploration that he accomplished over his 28 years of wandering through the northwestern regions of this continent. As one who himself has undertaken just a minuscule scope of exploring the watersheds of Northwestern Oregon, David Thompson stands out as a shining example of diligence, perseverance and intelligent observation along the way.

Say, you got a nice blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Much obliged.

Are the pictures on your blog in the public domain?

Many of the pictures are my own, some are scanned from books, etc. I am not totally in line with permissions for every picture…